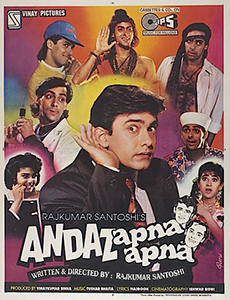

In an interesting development for all the movie (and IP) buffs, recently the Delhi High Court passed an interim injunction order against unauthorized use and commercial exploitation of character names, traits, and dialogues of the popular Hindi film “Andaaz Apna Apna”. Kartik Sharma takes a look at the order and explains how it, inter alia, fails to take a nuanced view towards personality rights, character merchandising, fair use and more. Kartik is a fourth-year student at the National Law School of India University. His previous posts can be accessed here and here.

Too much, Yet Too Little: An Examination of Delhi HC’s “Andaz Apna Apna” Interim Order

By Kartik Sharma

Who does not know about ‘Andaz Apna Apna’? (If you still haven’t watched it, highly recommended though). This cult classic comedy was the cynosure of IP law recently where the Delhi High Court granted a wide ranging interim injunction protecting the movie’s different intellectual property assets from unauthorized use and commercial exploitation.

The present suit has been filed by Vinay Pictures, the production house helmed by the late Vinay Kumar Sinha, who had produced Andaz Apna Apna in 1994. To better understand the case, it is integral to also discern the ambit of different IP rights that the plaintiff was asserting in its plaint. In para 34 of the order, the Court noted the plaintiff’s submission that it owns the rights in title, format, character rights, dialogues, dialogue delivery, mannerism, style of characters, costumes, along with all underlying literary, dramatic, and artistic work in the film. Interestingly, the plaintiff has also referred to trademark registrations pertaining to the film in its favour. Since we do not have access to the plaint, one can only surmise as to the exact registrations that were cited in favour of the plaintiff’s case.

My first impression was: That is a lot of things that the producers are claiming rights in, proprietary objects that lie beyond the textual contours of the coverage offered by the Copyright Act. Para 36 of the order expands on the plaintiff’s contentions by specifically referring to the iconic characters of the movie: Crime Master Gogo, Amar and Prem, and Teja. And finally, there is a reference to the iconic dialogues and catchphrases from the movie that the plaintiff claims have acquired secondary meaning and exist in a strong proprietary nexus with the plaintiff.

The infringing activities of the defendants can be classified under three broad heads: the sale of unauthorized merchandise on online platforms; registration of domain name, containing the movie’s signature phrase, used to host the sale of infringing products; and generation of artwork (including stickers and videos) using generative AI.

The crux of the contentions was that the infringing activities led to immense prejudice to the plaintiff, including grave economic and personal harm. It led to the violation of the plaintiff’s right to undertake commercial exploitation of the intellectual property flowing from the movie.

On that basis, the Court issued an injunction prohibiting the defendants (including John Doe parties) from creating any kind of content (images, AI generated content) that is a derivative of the film, selling any form of merchandise, offering any form of content under the name ‘Andaz Apna Apna’. The concerned defendants (MeITY,etc.) were also ordered to take down all the infringing links, websites etc. and further liberty was given to the plaintiff to implead parties that commit such infringing activities in the future.

A bird’s eye of the case reveals a judicial effort to protect the plaintiff’s rights in the movie as one monolithic body of work, without any exploration of the nuances involved in the differing nature of protection of the constituent elements of the movie. It is more than obvious that the different assets in which the plaintiff was asserting its rights (literary, dramatic works, characters, mannerisms, etc.) vary in their definition and the associated bundle of entitlements. The order however does not go into the legal niceties of each of these categories and operates on a much more generalized understanding of harm caused to intellectual property through the broad-stroke use of terms like dilution, tarnishment, and personal harm.

Firing All Shots, Something Should Hit

Now I would discuss some specific aspects of the interim order that merit attention. The engagement with each will be brief, in the interests of the blog length and considering that the main purpose of this post is to initiate and nudge these lines of inquiry. The first is the copyright protection claimed for the characters from the movie. The Copyright Act 1957 does not explicitly contain fictional characters as a discrete protected category. However, judicial interpretation over the years, as has also been done across multiple jurisdictions, has extended the law’s protective ambit to fictional characters as well. (Samridhi has covered this issue quite comprehensively in her blog post on the Taarak Mehta case). The Bombay HC in its 2016 ruling in Arbaaz Khan v Northstar Productions unequivocally held that copyright can subsist in a character fully realized and developed with unique characteristics and traits. As a general principle, the Court said, the unique (i) portrayal as well as the (ii) “writing up” of that character would be capable of protection. So yes, as a general rule, the beloved characters of “Andaz Apna Apna” do stand to be recognized as protectable categories of copyrightability. However, the Court missed out on taking the next step: to actually ascertain whether they satisfy this legal criteria or not? Justice (Retd.) GS Patel had quipped in Arbaaz Khan that Chulbul Pandey may have some distance to cover before he can reach Mr. Bond’s shaken-not stirred gold standard.

The above proprietary entitlement by way of copyright will vest with the producer of the film. There is another angle to the story, however, which is the publicity right in relation to the characters. The right of publicity, in its simplest articulation, entails an individual’s right to control the commercial value and exploitation of his name or picture or likeness and prevent others from unauthorizedly misappropriating the same for commercial benefits. Usually, the concept is linked to real-life celebrities but nothing prevents the same to be used in respect of fictional characters. Insofar as the law and general practice goes, this right of publicity in characters is held by the producer of the film. What usually happens is that the actors contractually license out this right of publicity in the characters they play, to the producer, therefore vesting the publicity right in that fictional character with the latter. The plaintiff production company in Applause Entertainment v Meta, for example, had claimed proprietorship over the publicity rights and character rights in the webseries “Scam 1992: The Harshad Mehta Story”. While discussing the case with Prof. Aakanksha Kumar, she pointed out an interesting argument that problematizes the holding of rights in fictional characters by producers. A fictional character is not just a visual static image of a dressed up person; the way that character is acted out in the cinematographic film forms a part of its conception. To constitute this, the contribution made by the concerned actor is also equally integral in addition to the scriptwriting. Often in personality rights cases concerning celebrities, the plaintiff celebrities have raised arguments that trace the distinctive speaking style, persona and mannerisms to their specific personhood. Examples would include the Anil Kapoor case and the Rajnikanth case. This also props up possible lines of analysis regarding the exact scope of protection offered to fictional characters and whether a demarcation of rights should be made between the producer of the film and the performers (actor) who played that character in that movie. All these thorny issues aside, the Court did not go into this Right of publicity at all. The order has no mention of it, so it might be that the same was not raised at all?

But there is something that is even more relevant: character merchandising. This involves the commercial exploitation of fictional characters through their utilization for the sale of various goods and services. Case law on this is scarce in India. Nevertheless, Star India v Leo Burnett is a prominent instance where character merchandising constituted one of the major legal issues. The Court there, while articulating the concept and the concomitant legal doctrine, observed that the characters in question have to exist in such a manner that they transcend the particular entertainment form (movie/show) they are a part of and can exist independently as commercially exploitable commodities. What the plaintiffs in Star India had alleged was the tort of passing off on the basis of character merchandising, which the Court was unable to find owing to various reasons. In the Andaz Apna Apna case, there is also a reference to passing off as part of the plaintiff’s claims against the defendants. Since misrepresentation is one of the three ingredients of passing off[the other two being (i) existence of goodwill or reputation, and (ii) actual or likely loss/damage due to defendant’s actions], one would expect a proper inquiry for this on the Court’s part. In para 40 of the order, the Court sweepingly refers to tarnishment, dilution, and mistaken association of the defendant’s good with the plaintiff as having been found to be happening in the factual matrix; there is a glaring omission of the distinctive conceptual underpinning of these concepts and constitutive elements. The Court inferred that the infringing products are likely to be inferior and the customers would be purchasing those goods under the mistaken impression of the source being the plaintiff’s legitimate commercial endeavours. No further reasoning or evidence to back up these observations was provided.

Going the Next Mile? Some More Missed Chances and Parting Thoughts

After giving some more thought to the order, I came up with certain other possible dimensions pertaining to trademark and copyright infringement. These are just preliminary thoughts and readers are free to agree/disagree with the actual implications.

The ‘fair use’ of commercial speech?

One, the Court might have wanted to assess trademark infringement by explicitly drawing upon the statutory prerequisites given in Section 29 of the Trademark Act, rather than rendering bare bone findings in favour of the plaintiff. Moreover, could the defendants have possibly invoked the doctrinal shield of nominative fair use? The AI-generated stickers and visual content could be looked at as creations along the lines of parody/satire, or more broadly as a consumption of humorous content that is more than just a plain incidence of use of a trademark in the course of trade. Delhi HC itself, in the Jackie Shroff case, recognized that spoof videos in the nature of parody/meme content are a form of artistic expression and can in fact contribute to the popularity of the celebrity figure in question. Even if the commercial angle to the use by defendants is conceded, the law still grants protection to commercial speech as well, as was most recently seen in the RCB Uber case. Similar queries can be raised for fair use doctrine in Copyright infringement. And finally, is the use of isolated dialogues on merchandise like T-shirts, etc, sufficient to constitute infringement of the plaintiff’s rights in the literary work? One may wish to allude to de minimis doctrine as a feature the court should have deliberated upon.

Gavel meets Culture:

Apart from the specific doctrinal holes that can be poked, the tenor and overall nature of the order reveals a more systemic issue: the grant of far-reaching injunctive remedies on the bedrock of scarce judicial reasoning and scrutiny into the plaintiff’s case. When a number of conceptual categories within the umbrella of IP law are invoked by the right-holder in enforcement actions, it is incumbent upon the court then to undertake a diligent analysis of each of the causes of action. Just because it is a preliminary injunction, this factum does not mean that an economical approach to providing reasons will be justified: the ideal of a sufficiently reasoned judicial order remains ever-present.

An order bestowing such extensive remedies on the right-holder is reflective of a very particular conception of IP that neglects the other objectives that IP assets further. Social-planning theory, for instance, touches upon the relevance of IP rights towards the promotion of a robust intellectual and cultural milieu. To talk about the case in particular, take the instance of the use of AI-generated stickers and other communicative tokens. The right-holder is not losing anything through the utilization of movie dialogues and characters for purposes that would fall within the category of parody or memes, or even if they constitute an addition to the communicative vocabulary in the digital space. In fact, it is through this circulation and appearance in the broader, day-to-day cultural context that also contributes to the sustenance of the movie’s legacy The movie’s underlying creative components therefore do not exist merely as commercially exploitable goods, but rather as a part of pop-culture as well. Only time will tell whether this umbrella of personality rights will get messier with time or not.

My big thanks to Prof Aakanksha Kumar for helping me navigate this super-complex world of ‘personality rights’, characters, and pop-culture. Many of the arguments in this post owe intellectual debt to her work.