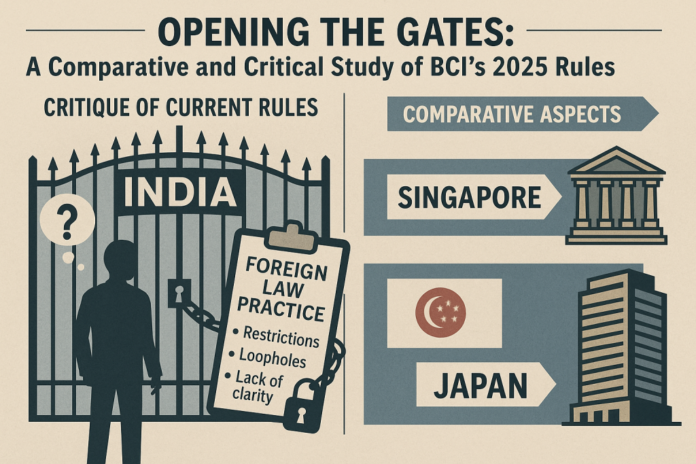

In Part One, we critically examined the BCI’s 2025 Rules, highlighting the legislative gaps, regulatory inconsistencies, and uneven burdens placed on Indian lawyers.

Lessons from Global Legal Hubs

It cannot be denied that the Indian legal industry is taking a definitive step toward global integration and liberalisation with the introduction of the new BCI Rules. However, we must remember that as we charter hitherto unexplored territory, it is both prudent and necessary to look outwards at established international legal hubs, like Singapore and Japan, that have already grappled with the same challenges and dilemmas that we face now, framed by the core question: to liberalise or not to liberalise, and if yes, by how much?

Both jurisdictions adopted contrasting strategies with distinct outcomes in this regard. Much like India, Japan took the cautious route and is currently midway through its liberalisation journey. On the other hand, Singapore is a fully liberalised and thriving international legal hub. It is important for us to study both as a nation that is just starting this journey.

The Japanese Approach

The Japanese legal ecosystem bears many similarities to the traditional Indian attitude when it comes to allowing the entry and operation of foreign law firms in the domestic arena. Historically characterised by a protectionist tilt, Japan’s approach to liberalisation has been slow, deliberate, and cautious.

Initially highly restrictive, Japan began to open its legal market in 1986 by enacting the “Gaikokuho Jimu Bengoshi Ho,” also called the “Registered Foreign Lawyer Act.” It allowed foreign lawyers, called Gaikokuho Jimu Bengoshi (“GJBs”), to register and provide legal services related to the laws of their home jurisdictions. However, their scope of practice was very limited, and they could not practice Japanese law or form partnerships with Japanese lawyers (called bengoshi).

This restricted range of operations was gradually broadened when, in 1994, the GJB Act was expanded to allow specific joint enterprises between the GJB and bengoshi for matters involving foreign and Japanese law, along with the introduction of profit-sharing clauses.

Further expansion came via reforms in 2003 and 2005, which allowed GJBs to employ bengoshi, in addition to sanctioning full partnerships between registered foreign law firms and domestic law firms and significantly easing restrictions on the area of practice. However, the most significant step towards liberalisation came via an official announcement on April 1, 2010, which allowed foreign law firms to set up and operate via domestic offices in Japan.

Recently, in 2020, via Law No. 33, Japan greatly expanded the scope of operation of foreign lawyers in international arbitration and mediation cases and established the Joint Corporation System, allowing GJBs to form incorporated legal entities jointly with bengoshi and birthing the possibility of a client having access to both Japanese and international legal services at one destination.

These gradual but increasingly progressive amendments have allowed Japan to open up its legal sector in a controlled and coordinated manner, at a pace that is suitable for the needs of the Japanese legal ecosystem. The Japanese Federation of Bar Associations has intricately balanced the need for liberalisation and globalisation with the concerns of protection and integrity of the domestic legal industry.

The qualitative impact of these measures has been noteworthy. The corporate segment of the Japanese market is projected to grow with an excellent Compound Annual Growth Rate of 4.11%. This growth is primarily propelled by the global expansion of legal firms in Japan, which creates the need for specialised corporate expertise in fields like international compliance and trade laws and international arbitration and mediation.

However, there are still challenges, primarily in the form of lingering stringencies in the registration and regulatory environment. 70% of foreign law firms in Japan cite regulatory challenges as a major obstacle to business operations. Additionally, the slow pace of liberalisation has also been criticised. It is argued that this pace is causing the Japanese legal environment to lag behind, and that it will be outpaced by the rapidly growing international legal landscape.

For India, the key takeaways here are taking a methodical approach of progressive expansion, counterbalanced by considerations of domestic needs and international obligations. This approach will ensure that domestic firms are not overwhelmed while allowing them to benefit from global expertise.

The Singapore Model

Singapore falls on the other end of the spectrum as a jurisdiction that has already established itself as one of the most prominent international legal hubs. With nearly 150 foreign law firms already operating in Singapore, combined with its dominance as one of the world’s most preferred seats of arbitration, Singapore manifests a success story of legal liberalisation.

This was the result of nearly three decades of meticulous efforts to bring about effective reform in the legal industry. Historically, Singapore’s legal system, inherited from the British colonial regime, just like ours, was largely isolationist in nature. Foreign firms were allowed to operate but were restricted to offshore work, primarily in an advisory capacity. Until 2000, Singapore had no written laws that provided for the regulation of foreign law practices in the domestic jurisdiction.

With rapid industrialisation and internationalisation in the 1980s, the government identified the arena of legal services as one that could possibly contribute to future growth if it could be enhanced to attract foreign law practitioners, and this led to the Singapore Legal Profession (Amendment) Act of 2000.

This legislation introduced avenues for collaboration between foreign law practices (“FLPs”) and local law practices (“LLPs”) by allowing Formal Law Alliances (“FLAs”), which provided a framework for FLPs and LLPs to create a formal association, sharing office premises, resources, and permitting co-branding. Additionally, it established the concept of Joint Law Ventures (“JLVs”), which refers to a company set up and jointly owned by Singaporean and foreign law firms. They could operate as a new, separate legal entity and could bill as a single firm.

This was a significant step, but foreign lawyers were still restricted from practising Singapore law directly, except in limited contexts through the JLV or FLA structure with local partners.

The next wave came via the Qualifying Foreign Law Practice (“QFLP”) Scheme, which granted specific FLPs licenses to practice Singaporean law across all sectors except for domestic litigation and general practice. This scheme has generated more than $3.07 billion in offshore revenue since 2013.

Additionally, the success and popularity of the Singapore International Arbitration Centre further demonstrate the effectiveness of its legal liberalisation initiatives and its position as a top international arbitration hub.

All of this has been made possible because of the measured and phased approach that Singapore adopted. It was the result of a combination of progressively opening its doors to foreign law firms and lawyers while building strong domestic institutions and fostering a supportive legal ecosystem.

The key takeaway for India is to increase the focus on creating a continuous, ongoing process of review and adaptation. We could look to replicate the working of the Singapore Ministry of Law, which regularly consults stakeholders to assess whether existing schemes are effective or not, and engages in detailed periodic assessments to consider possible future reforms to meet market needs and capitalise on opportunities.

However, we must also remember that the picture is not all white. An increased influx of international players meant intensified competition, and the brunt of it was felt by local small and medium-sized practices (“SMPs”). A “war for talent” broke out, and SMPs struggled to attract and retain top lawyers, who now had better earning opportunities at the larger and better-equipped international firms.

Another crucial fact to keep in mind is that Singapore’s liberalisation was accelerated by a combination of unique domestic circumstances that India does not enjoy. In addition to being a leading global trade centre, Singapore enjoys the advantages that come with being a small, unified city-state. This allowed for the successful execution of a top-down approach with minimal internal resistance. India, on the other hand, operates on a scale that is much larger in magnitude. Consequently, a similar rapid top-down approach is not a feasible option for us.

Recommendations and Conclusion

Japan’s liberalisation shows the merits of a careful and gradual process and warns us against being overly cautious. Conversely, Singapore’s approach emphasises the benefit of a progressive and consultative process while demonstrating the risks of subjecting small-scale domestic firms to unregulated foreign competition.

Prior to undertaking full-scale liberalisation, we must invest in the capacity building of local firms and lawyers to make them capable of standing on an equal competitive ground with foreign firms and not be left behind. The move to / must not present foreign firms as superior alternatives to domestic firms.

For this, government-backed skill development initiatives and partnerships with foreign firms involving training and knowledge-sharing are needed. An excellent model of how this can be done is through Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 plan, which envisions a new licensing framework for foreign law firms. Under this regime, foreign firms that apply for licenses need to present annual work plans with required knowledge-transfer provisions while also providing a minimum of 20 hours of training to all Saudi employees.

In addition, there should be a mechanism for reviewing the progress and measuring the effect of liberalisation efforts. We need to establish a specific regulatory body or specialised department within either the BCI or the Law Ministry, which should be responsible for observing the impact of initiatives in real-time, interacting with stakeholders, and suggesting optimal policy changes, similar to Singapore’s Legal Services Regulatory Authority.

The 15th Law Commission has also made recommendations in this regard, proposing a framework for the adoption of Article XIX(2) of the General Agreement on Trade in Services. Implementation of this clause in a proper manner would facilitate liberalisation without compromising national policy goals.

As we progress towards integrating the Indian legal environment with the global mainstream, we are at a crossroads. Many opportunities exist, but so do complex challenges. While Singapore’s dynamism is aspirational and Japan’s caution is relatable, India’s path must uniquely be its own.

Therefore, the need of the hour is an approach that is adaptive and prioritises rectification of existing lacunae, legislative amendments to solidify the new rules and ensuring a level playing field. Only through such an approach can we hope to harness the full potential of these reforms while also ensuring that they are in line with our legal heritage and spirit.

Kush Taparia and Apoorv Brahmamitra are second-year law students at National Law University, Jodhpur. Kush has a keen interest in Competition Law and Criminal Law, while Apoorv is particularly inclined towards International Law and Competition Law.

Ed Note: This post was edited by Hamza Khan and published by Baibhav Mishra from the Student Editorial Team.