[ad_1]

This post is co-authored with Aditya Bhargava, a fourth year law student at NLSIU Bengaluru and who has also contributed to the blog previously (here).

This blog usually covers a wide range of trademark disputes; however, most of them are adjudicated at the high court stage. This piece, in that regard, is slightly different—it comes straight from the Supreme Court of India (‘SC’). It’s none other than the great battle between Blenders Pride and London Pride.

For the uninitiated, this case reached the SC through an appeal challenging the findings of the Madhya Pradesh High Court’s DB. Nothing changed; the SC upheld the decisions of the lower courts, refusing to grant an interim injunction against the use of the mark ‘LONDON-PRIDE’ for whiskey.

In this post, we refer to the core decision very briefly since that is mostly concerned with the traditional law on trademark infringement and passing off analysis. What we aim to spend time on is the Court’s interesting obiter on the nascent doctrine of post-sale confusion. It is here that the judgment becomes both forward-looking and, arguably, falls short of a thorough analysis.

Background of the Case:

The appellants, who have held registered trademarks for ‘BLENDERS PRIDE’ since 1994 and ‘IMPERIAL BLUE’ since 1997, initiated legal action after discovering the respondent’s ‘LONDON PRIDE’ whiskey on the market in 2019. A key part of their argument was the allegation that the respondent was selling its product in bottles that were embossed with the appellants’ own house-mark, ‘SEAGRAM’S’, and their ‘IMPERIAL BLUE’ mark. They contended that this practice constituted a case of trademark infringement and passing-off.

The SC dismissed the appeal, focusing on a core principle of trademark law: marks must be evaluated in their entirety, not by dissecting them. The Court reasoned that the word ‘PRIDE’ is a common, laudatory term and its mere presence does not automatically create deceptive similarity. When viewed as a whole, ‘BLENDERS PRIDE’ and ‘LONDON PRIDE’ were distinct in their structure, sound, and appearance. The Court rejected the appellants’ attempt to combine elements from their different brands to form a “hybrid” claim against the respondent, deeming it an untenable argument.

Reckoning with Post-Sale Confusion:

Towards the end of the judgment, the Court commences its foray into the confusion doctrine. The discussion begins with the Court noting the doctrine’s recognition in the USA and most recently in the UK (through the Iconix v Dream Pairs ruling by the UK Supreme Court). In India, the doctrine is relatively novel. What it seeks to remedy, the Court notes, is the harm to the distinctiveness and perceived exclusivity of the genuine product, also linked to a dilution of the brand’s goodwill.

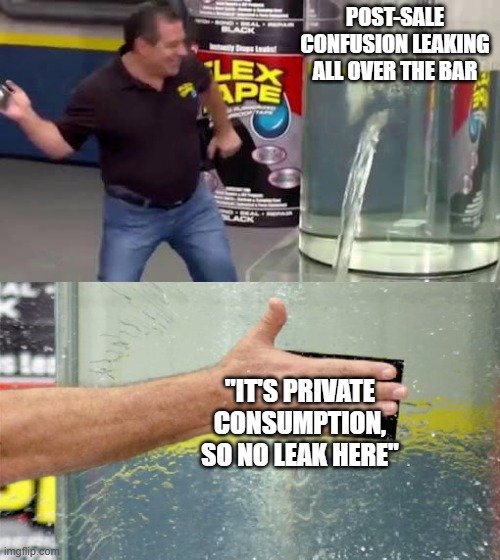

There are two interesting things done by the SC: First, the Court somehow concludes that the goods here (whiskey bottles) are only for private consumption and not intended for public display, therefore negating the need for post-sale confusion’s application to the facts. Second, the Court extracts paragraphs from UKSC’s Iconix ruling. However, if one reads Iconix, it’s easy to realize that Pernod Ricard missed out on a lot of the directly relevant parts of the UKSC judgment concerning the issue of post-sale confusion.

The reason this post is dedicated to post sale confusion is that the SC has recognized the relevance of this doctrine to future cases in India (¶ 40.4). Even though it’s obiter, future cases coming up before lower courts will likely cite Pernod Ricard for claims based on post-sale confusion. Caveat: the doctrine is not without its fair share of criticisms, including its alleged incompatibility with the core principles of trademark law. We thus also caution against an impulsive transplant of the doctrine into India.

A Taxonomy of Confusion—Locating the Harm:

As Professor Ilanah Fhima highlights, a key controversy surrounding post-sale confusion is the difficulty in locating the type of harm that trademark law has traditionally sought to prevent. Not all forms of post-sale confusion are alike, and the harm—or lack thereof—varies significantly. Using Prof. Fhima’s framework, we can see a spectrum of confusion:

- Downstream Confusion: It occurs when a non-confused purchaser gives or sells the product to a third party who is confused. The classic example, as noted in the UK case of Arsenal Football Club plc v Reed, involves counterfeit merchandise. If a person knowingly buys an unofficial “ARSENAL” scarf and gifts it to a friend who is unaware of its origin, and that scarf then quickly falls apart, the friend will attribute the poor quality to the Arsenal brand itself. The harm is clear: damage to the trademark owner’s reputation and loss of future sales.

- Bystander Confusion: This form is more complex and controversial. Here, a bystander observes the purchaser using the goods and is confused as to their origin, which might affect the bystander’s future purchasing decisions. This was the scenario in Iconix, where onlookers might see someone wearing Dream Pairs’ boots and mistake the logo for Umbro’s. Fhima points out, citing scholars Raustiala and Sprigman, this confusion can often be “fleeting and without consequence”. An observer might be confused for a moment, but this does not necessarily translate into a lost sale or reputational harm for the brand owner. The UKSC in Iconix found infringement based on bystander confusion without explicitly identifying the harm that might arise from it.

- Status Confusion: This applies particularly to luxury goods, where peers of a non-confused purchaser see them with a lookalike product and falsely believe the purchaser possesses the status, wealth, or taste associated with the genuine article. While this might dilute the brand’s exclusivity on a large scale, it is highly questionable whether trademark law’s role is to protect a brand’s “snob appeal”. Prof. Fhima notes, this form of confusion has not been recognized as a basis for infringement in the UK.

This framework reveals that a blanket adoption of “post-sale confusion” is problematic. The question for a court should be: what is the nature of the confusion, and does it cause a legally cognizable harm to the trademark’s core function of source identification?

Applying the Lens to Pernod Ricard:

In order to critique the ‘two interesting things’ mentioned above, a brief explanation of Iconix is important. The case involved a dispute between Iconix, the owner of the Umbro sportswear brand and its “double diamond” logo, and Dream Pairs, a seller of footwear that used a similar-looking logo. The UKSC was asked to decide two key issues: first, whether extraneous factors like the post-sale viewing angle could be considered when assessing the similarity between marks ( “Similarity Issue“), and second, whether post-sale confusion could be a standalone basis for infringement even if there was no confusion at the point of sale (“Confusion Issue“).

The Court answered yes to both (¶ 60 & 86). For the assessment of similarity between the two marks, the UKSC held that realistic and representative circumstances in the post-sale environment must be considered. The court cannot just compare the two marks in isolation; it is also important to factor in the realistic scenario in which the concerned products will be seen by the public. This includes the context, viewing angles, and distance from which the marks are perceived. On the second issue, the Court unequivocally held that post-sale confusion can, in an appropriate case, be a self-standing basis for infringement, without the need for it to be happening in relation to a subsequent transactional context.

Coming to Pernod Ricard and our whiskey bottles. If one had to carry out a post-sale confusion analysis, Iconix dictates that the court compare the two marks by visualizing the situation the products would find themselves in, since that is where the relevant public will be interacting with the marks post-purchase (¶ 60-66). Indian SC seemed to grasp this. However, and we say it as simply as possible, there is no factual basis for the assertion that liquor bottles are “not intended for public display and are for private consumption”. As the legal fraternity is well-aware, whiskey is served at social gatherings, displayed on bar shelves in pubs and restaurants, and shared among friends. These examples buttress the aspect of public display that is clearly attracted here. What appears to be the underlying assumption of the Court’s observation is the social stigma attached to alcohol consumption; that it is not for public display, that liquor is a thing of the private domain. But value-judgments of this nature cannot inform the legal appraisal of doctrines given they are also disjunct from social realities. By summarily dismissing the possibility of public display(¶ 40.4 – 40.5), the Court sidestepped the need to engage with the very analysis that Iconix mandates.

This leads to the second failing. By extracting the generic principles on trademark law from Iconix—such as the definition of the average consumer and the scope of appellate review —the SC missed the core of the UKSC’s ruling. It failed to engage with the substantive reasoning on why post-sale confusion is actionable and how the similarity-analysis must adapt to the post-sale context.

The Pernod Ricard judgment introduces a new area of trademark law in India, but its brief analysis requires careful development by future courts. Without a clear focus on tangible harm and rigorous assessment of existing jurisprudence and scholarly works, the doctrine risks becoming a remedy for abstract problems, illogically extending trademark law to protect against possibilities rather than real damage to a brand’s identity.

Thanks to Swaraj and Praharsh for clarifying the nuances of whisky v whisk(e)y!

[ad_2]

Source link