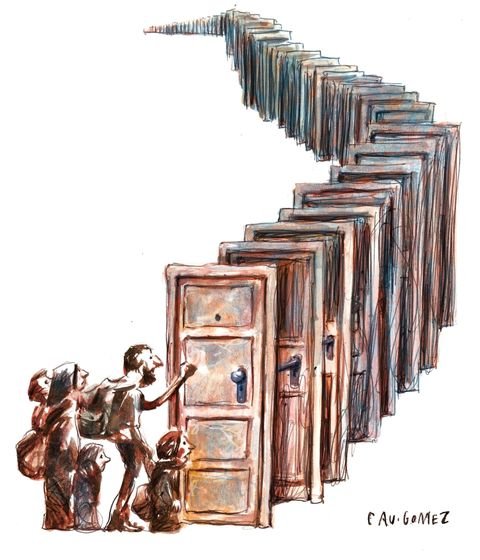

The previous part discussed the principle of proportional burden sharing and argued that it resolves the refugee problem. This part underlines the changes in the International Legal Landscape regarding refugees, especially climate refugees to argue that the principle of proportional burden sharing is more likely to be satisfied now than earlier.

Why It is More Likely to Be Satisfied Now

Refugee migrations in the last century tended to be localized owing to a variety of factors. This led to a sense of insularity amongst non-affected countries. Thus, the principle of insurance which forms the basis of proportional burden sharing was ineffective in persuading unaffected states to agree to this scheme. It is argued that the changing contours of the refugee crisis is a strong factor in favor of adopting of this insurance-based proportional burden-sharing model.

It is argued that the rise of climate refugees has shattered the earlier insularity. Even if the terminology “climate refugee” is not currently recognized under International Law, it is argued that the principle of “non refoulement” has firmly entrenched itself in International Human Rights Law (“IHRL”). Thus, a State may not turn away a person seeking protection if is aware that “certain death or harm” awaits that person on return. The scope of this principle is explored in the next section, and it is sought to be proven that a combination of factors—of which climate change is prominent—may meet this threshold.

Presence of Climate Refugees

The phenomenon of climate refugees presents the biggest challenge to the conventional modes of treatment of refugees. The definition of refugees given by the 1951 Convention does not cover climate refugees, however the number of people getting displaced owing to climate change has consistently risen over the past few decades. Since 1880, the sea level has risen by around 24 centimeters, a third of which has been since 1990. This rise has exposed an estimated 745 million people living in coastal areas and islands to the risk of floods and storms. It is particularly felt in Small Island Developing States which experience a drastic increase in flooding. Apart from the direct impact on life, this has had an impact on the environment in these states. Changes like the salinization of freshwater, degradation of soil and others are increasingly making these areas unlivable. Thus, climate change and its consequences have had a detrimental effect.

There is intense debate on whether the definition of refugees should extend to include climate refugees. However, it is argued that in the instance where a place becomes completely uninhabitable, there exists no other alternative but to accept them. Necessity propels permitting the refugees to stay in a country because certain death awaits in the event they are sent back. Thus, the principle of insurance remains at play owing to the sudden and permanent influx of refugees, specifically in cases where the damage is permanent. In Teiotia v. New Zealand, it was observed that people facing climate change impacts which violate their right to life cannot be repatriated back to their country of origin (at p. 11). Another strong sign showing the legal recognition of climate refugees, is the recently signed agreement between Australia and Tuvalu to settle the citizens of the latter permanently in the instance Tuvalu submerges.[xxvii] This is the first-time climate induced migration has been formally recognized. Furthermore, it has been estimated that this century could see a loss of over 10,000 km^2 of land, leading to displacement of up to 5 million people. These are merely statistics for the most extreme effect of climate change where the home country completely submerges, thus leaving the people with no alternative but to flee.[xxviii] As will be demonstrated in the next section, a strong case can be made for the application of the non-refoulement principle under IHRL to protect these people from being sent back. Furthermore, it is also shown that the scope of non-refoulement under IHRL is much wider and covers other instances of displacement as well.

The Principle of Non-Refoulement under IHRL

The principle of non-refoulement is a negative obligation on states under IHRL. While IHRL recognizes the right to seek and enjoy asylum, under Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“UDHR”), the same has been held to be non-binding in nature. Thus, the principle of non-refoulement becomes paramount as a shield for displaced people worldwide. Its importance is underscored by its express or implied mention in multiple treaties worldwide. Its scope, is broader than its counterpart under Article 33 of the Refugee Convention. The principle under Human Rights law operates without territorial or personal scoping restrictions like the five qualifying grounds of persecution. It is applicable as soon as a person can prove substantial risk of any type of harm, recognized either by the treaty or Customary International law.

Can the Principle of Non-refoulement Be Extended to Cover Persons Displaced by Climate Change?

There may be two types of situations: firstly, where the cause of displacement is attributable to a combination of factors among which climate change is one; and secondly, where the cause for displacement is only climate change In the first instance, the migrants may be considered as refugees under the Refugee Convention if they fulfil the definition. Furthermore, the principle of non-refoulement under IHRL may comfortably apply in their case. In the second situation—where the sole factor for displacement is climate change—there exist competing viewpoints in academia and the Courts about whether the non-refoulement principles is applicable.

The case of Teitiota v. New Zealand considered a situation where the victim, a Kiribati citizen, filed a case against the New Zealand government for failing to grant him refugee status. He contended that the lack of drinking water, conflict, continuously shrinking agricultural land owing to rising sea levels and flooding made Kiribati unlivable. The Human Rights Committee recognized that the states have a duty to protect the right to life by addressing conditions which may pose a threat to it. It stated that a consideration of cumulative facts indicating the general human rights condition in the author’s country of origin must be done. It further called for a wide interpretation of the right to life and stated that states have a positive obligation to prevent displacement and relocate people adversely affected by disasters caused or related to climate change. It extended the applicability of Articles 6 and 7 of the ICCPR laying down the principle of non-refoulement to climate change. However, the majority were unable to find an immediate and personalized risk to Mr. Teitiota. It considered the time period of 10-15 years as being sufficiently far in the future and coupled with the measures undertaken by Kiribati, made a strong case against Mr. Teitiota. Another factor, though not mentioned, which may have played a role in influencing the decision of the Committee was that Mr. Teitiota was the sole applicant. Essentially, the Committee was unwilling to apply the principle owing to the long duration before which the expected disaster was to occur.

This emphasis on duration begs the fundamental question asked by Mr. Muhumuza in his dissent as well, that “whether is it necessary for the protection of life to wait for deaths to be very frequent and numerous in order to consider the satisfaction of the threshold of risk.” Suppose owing to the effect of continuous floods and other disasters, freshwater becomes saline, agriculture yield drops and other necessities are also affected and the Country of Kiribati becomes unlivable: would the threshold be satisfied then? The situation might be different in a larger country blessed with more natural resources and more economic strength so this analysis may not be applicable there. However, it is necessary to consider whether this “stamp of approval” provided by extreme and potentially irreversible conditions is necessary for the rights of these people to come in play.

In this context, it becomes more necessary to take a more humane approach to human rights and not make them the rights of last resort. Regarding the aspect on personal risk, Jane McAdam draws an analogy to the concept of “persecution” under Refugee Law. She says that in generalized cases of violence, it is incorrect to limit the concept to direct and personal risks. Similarly, in cases of indiscriminate climate change, the aspect on special personal risk should not be looked at.

Additionally, with respect to the aspect on temporal difference, McAdam suggests a “likelihood” test instead of simple rejection of events with a time gap. The rationale, as suggested by her, is that imminence is relevant for procedural questions and not substantive ones (at p. 11). Thus, the test for substantive claims is the likelihood of harm. It is further suggested that a test like the test of “well-founded fear” under refugee law which looks at the presence of “substantial grounds for believing the risk of irreparable harm” is suitable. The Supreme Court of the United States laid down the scope of this test in the judgment of Immigration and Naturalization Service v Cardoza-Fonseca. It held that a well-founded fear need not be completely certain, it is enough that it is a reasonable possibility Adrienne Anderson further states that there is no temporal element to this test. Events far off in time may have the possibility of being more uncertain, but the test is structured to incorporate long term instances as well.

Lastly, regarding the aspect on mitigation measures taken by the origin state as a countervailing factor, it is argued that the UNHCR Guidelines on International Protection are instructive. The Guidelines recognize that armed conflict has a life of its own and multiple factors are involved in its spread. It is then suggested that to effectively ensure protection, the trajectory of harm should be looked at (at p. 16). The Guidelines lay down some indicators to aid the States in foreseeing the harm. Furthermore, they recognize that despite the mitigation measures taken by States to alleviate harm, crisis often spreads. Considering this analogy in the Teitiota judgment, the reliance placed by the committee on the mitigation efforts of Kiribati looks far-fetched especially where international law itself recognizes that the best State efforts may not be sufficient.

The case of Teitiota v. New Zealand opened the floodgates on the debate about the refugee status of people displaced by climate change. Furthermore, by recognizing the interlinkage between the IHRL principle of non-refoulement and climate change, a pathway to stronger protection of people displaced by climate change is shown. Essentially, this shows a move toward a mechanism for better protection of such people, driven by their basic right to life. In light of this, the principle of proportional burden sharing assumes paramount importance. This part has tried to show that it is in the interest of States to agree to proportionately share the burden of accepting refugees. The principle of insurance on which proportional burden sharing is based provides the reasons for this self-interest. In future, where the scale and intensity of these migrations is likely to increase owing to the adverse effects of climate change as well as other phenomena, this principle will provide a safety net by beleaguered States who are caught between international obligations and domestic protests.

Rudra Singh Krishna and Suhani Suri are undergraduate law student at WBNUJS, Kolkata.

Picture Credit: Cau Gomez/Cartoon Movement