[ad_1]

The author of this post is Akshay Singh , student of Law at RGNUL, Punjab

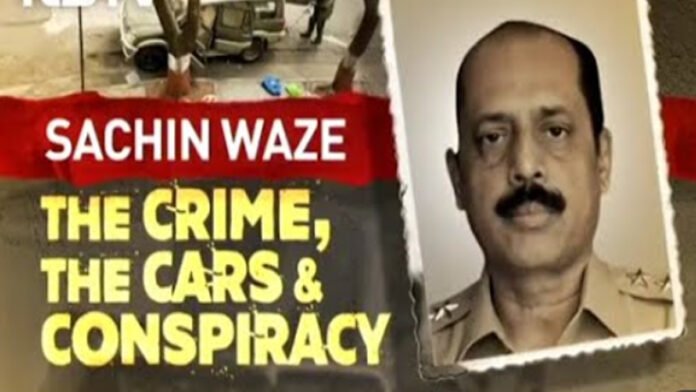

A threat letter, 20 explosive gelatin sticks, and an unclaimed SUV car found outside the house of India’s richest man culminated in the arrest of Assistant Police Inspector Sachin Waze(“Waze”) by the National Investigation Agency. He was subsequently ‘dismissed’ from police services by Mumbai Police Commissioner without even holding a departmental inquiry by invoking Proviso 2 (b) of Article 311(2) of the Constitution of India, 1950 ( “Constitution”). What caught everyone’s attention is that the dismissal of Waze came at a time when he is at loggerheads with the state government after he has addressed a letter to the NIA court alleging corruption in state government. The dismissal order which found a mention of his alleged misconduct concluded on the note that the competent disciplinary authority was satisfied that holding a departmental inquiry against him “will not be reasonably practicable.”

Eyebrows were raised as to whether the circumstances of the case were rare and such that it warranted the exercise of exceptional powers given to Disciplinary Authority under the Constitution of India or is it another example of mala fide exercise of power as the state government has an axe to grind with Waze? In the backdrop of these facts, it is important to bear in mind that the “Dismissal” carries a special significance in the life of a government servant as it is the highest level of penalty that can be imposed on a government servant and it ordinarily disqualifies him from future employment under any Government service. “A dismissal of a Government servant without a departmental inquiry” would therefore mean that not only a person is barred from being again employed in the government services but also the said dismissal is done without giving him a reasonable opportunity of being heard or conducting an inquiry into the allegations against him.

The Power of competent authority to dismiss without a departmental inquiry provided under the Constitution can only be exercised in three rare circumstances which are enumerated under Proviso 2 of Article 311(2) of the Constitution. A perusal of cases in light of the facts of the instant case reveals that the invocation of such extraordinary power in the instant case is highly questionable.

Interplay of article 310 & 311 of Constitution of India

Article 310(1) of the Constitution of India embodies the common law “Doctrine of Pleasure” in the sense that a government servant would be holding an office during the pleasure of the President/Governor, as the case may be. The pleasure can be exercised by President/Governor, either on the aid and advice of the Council of the Ministers or the authority specified under Article 309 of the Constitution. Three limitations to this power are enumerated under the Constitution are:

- 310(2) – An enabling provision which provides for compensation to persons having special qualifications, not being a member of defence/all-India/civil service, if before the expiration of the agreed period, the post on which he is appointed is abolished, or if he is required to vacate the post.

- 311(1)- No removal or dismissal by an authority subordinate to the appointing authority.

- 311(2)- No dismissal, removal or reduction in rank except after an Inquiry in which he has been informed of the charges against him and given a reasonable opportunity of being heard in respect to those charges.

The safeguards under Article 311(2) is not absolute and limited in in the sense that Proviso 2 to 311(2) contain three exceptional cases where the need of holding an inquiry can be dispensed with, namely-

(a) where he is dismissed or removed or reduction in rank on the ground of conduct which had led to his conviction in a criminal charge; or

(b)where the authority empowered to dismiss etc. is satisfied that for some reason, to be recorded by the authority in writing, it is not reasonably practicable to hold such inquiry; or

(c) where it is not expedient to hold such inquiry in the interest of the security of the state.

The Hon’ble Supreme Court of India and various High Courts over the years have cautioned the State governments and Central government, as the case may be, to not use the exceptional powers given by the Constitution in the circumstances where it is not warranted. The following analysis of the peculiar facts of Waze’s case in light of settled judicial principles will reveal that the invocation of the exceptional power was unwarranted in the present case.

Questions in Mr Waze’s case

Whether there exist reasons for satisfaction to hold that a Departmental inquiry is not reasonably practicable in Waze’s case? And whether the reasons given for satisfaction behind dismissing the departmental inquiry is in the public interest or a result of mala fide exercise of power?

To appraise the questions at hand in its full scope, it is important to reproduce some of the guidelines laid down by the Supreme Court in the landmark decision of Union of India v. Tulsiram Patel. The Supreme Court observed:

“a. The disciplinary authority must not disperse with the inquiry lightly or arbitrary or out of ulterior motives or merely to avoid the holding of an inquiry or because the Department’s case against the government servant is weak and must fail.

b. The reason for dispensing with the inquiry need not contain detailed particular, but the reason must not be vague or just a repetition of the language of clause (b) of the second proviso. For instance, it would be no compliance with the requirement of clause (b) for the disciplinary authority simply to state that he was satisfied that it was not reasonably practicable to hold a inquiry.”

What follows from the judgement is that the Disciplinary authority is in the best place to judge the prevailing situation in the light of facts and circumstances and there is no straight jacket rule which conclusively conveys that there exists reasonable impracticability. However, a perusal of the cases which involved the same exception would give certain common factors that have been considered by the courts over the years to ascertain the practicality of holding a departmental inquiry, namely:

- Whether the government servant is in a position to influence the witnesses and the Inquiry and prevent it from being conducted in an effective and impartial manner?

- Whether there is an atmosphere of violence/terror or of ‘general indiscipline and insubordination’ prevails which would render it impractical to conduct an impartial inquiry?

On First ground, In Waze’s dismissal order, apart from serious allegations of misconduct, it was specifically alleged that Waze tried to conceal and destroy the evidence which would incriminate him in a case, yet it has not been specifically mentioned by the Disciplinary Authority clearly that the result of his actions is such it is now not reasonably practicable to conduct an effective inquiry in an impartial manner. In absence of any clear-cut ground, the reasons mentioned are liable to be declared vague.

On Second ground, the dismissal order merely alleges that he is the central figure behind the Antilla bomb scare case which created terror in the mind of people, however, it is not enough to conclude that there exists a general atmosphere that would render it impossible to conduct an impartial inquiry.

Conclusion

Constitution-makers never intended to leave the government servants at the mercy of the arbitrary, capricious or mala fide exercise of the power by the government and therefore the intention behind giving such extraordinary powers to the Government is that it will only be used when overriding public interest and public good demands.

In the second case decided along with Union of India v. Tulsiram Patel, the said exception was invoked when the member of CISF resorted to willful and deliberate disobedience of orders and did gherao of supervisory officers and threatened to kill them if their demands are not met.

In the third case decided along with Union of India v. Tulsiram Patel, the said exception was invoked when they paralyzed the entire railway system and assaulted and intimidated other workers and senior officials.

In Satyavir Singh v. Union of India, the exception was invoked when the employees of Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) resorted to protest, strike and kept some people as hostages.

In Southern Railway Officers Association v. Union of India, the exception was invoked when the delinquent employee threatened to kill his superior officer and his family members.

A perusal of facts of all the cases hereinbefore mentioned reveals that even if the ‘allegations’ in the instant case based on which Waze is dismissed are assumed to be true, they are still not of such magnitude to justify not holding an inquiry. Further, there is no element of public interest or public good involved in the present case which warrants the recourse of the extraordinary power by the Disciplinary Authority. Even the finality clause under Article 311(3) which states that “the decision with respect to the satisfaction of circumstances, taken by the Disciplinary Authority will be final”, will not save the order as it does not dispense with the obligation on the part of the concerned authority to satisfy the court or the tribunal that the order passed and the satisfaction was arrived after taking into account relevant facts and circumstances and the satisfaction is not vitiated by mala fides. The dismissal order therefore looks indefensible specially in the light of ongoing tussle between Waze and Maharashtra Government.

Preferred Citation: Akshay Singh , Analysing the dismissal of Sachin Waze: A case of Unwarranted Invocation of Article 311(2) Proviso 2 of Constitution of India , The Criminal and Constitutional Law Blog, Published on 21st July 2021

[ad_2]

Source link