[ad_1]

Explaining the implications of the Bombay High Court judgment in Rupali Shah v. Adani Wilmer on the assignment of rights arising from the future use of a work, Arjun Ishaan discusses the position in the Indian Copyright Act on assignments and suggests policy amendments that may grant creators limited rights to renegotiate legacy contracts. Arjun is a 3rd year student at B.A.LL.B. (Hons.) at Dharmashastra National Law University, Jabalpur. He is passionate about legal research and staying abreast of new developments in law, especially in the field of Intellectual Property, Company Law and Arbitration Law.

Rewinding the Law: Are Pre-Digital Era Copyright Assignments Valid for Today’s Modern Tech Platforms?

By Arjun Ishaan

Imagine a musician in the 20th century assigning copyright to a song when music was distributed through tape recorders or radios only to find out decades later that the song has gained new commercial significance and is exploited by the assignee on new streaming platforms like YouTube, Spotify, etc. Can the artist sue the assignees for breaching the original agreement? This is the dilemma courts face today: do copyright rights granted before the digital era include the right to stream through modern and non-physical platforms?

A similar issue was dealt with by the Bombay HC in its June 11 order in Rupali Shah v. Adani Wilmer, where it was held that if the language of the original agreement between the parties doesn’t contain any express provisions limiting such exploitation, then it remains valid for digital use. This post critically analyses the judgment, outlines its implications, and argues for a policy change which grants creators limited rights to renegotiate in legacy contracts.

Decoding the Judgment in Rupali Shah v. Adani Wilmar Limited

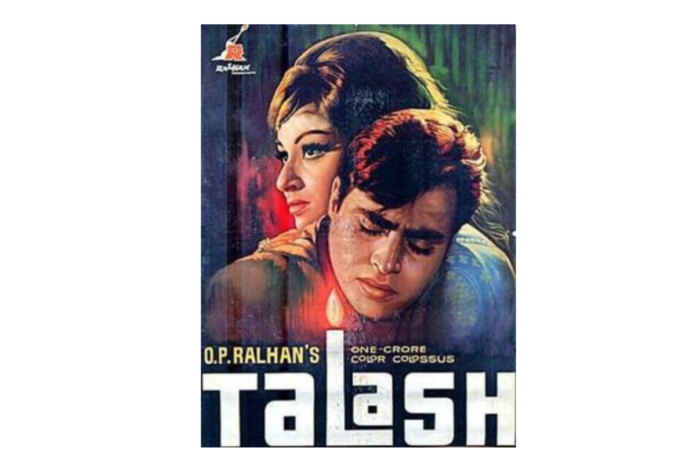

The main contention in the above case arose over the song ‘Meri Duniya Hai Maa Tere Aanchal Mein” from the movie “Talash”, produced by the late filmmaker O.P. Ralhan. He assigned the rights of the work to Saregama India Ltd in 1967, which in turn signed a licensing agreement with Adani Wilmar for the use of the song in a telephone advertisement. Rupali Shah, daughter of the late producer, filed a suit to restrain the defendants from using the song in commercial advertisements, arguing that the original agreement didn’t foresee digital use or streaming. The plaintiff’s argument was that modern digital methods to exploit the work could not have been imagined in 1967 and thus were outside of the rights assigned.

However, the Court ruled in favour of the assignees; it held that the agreement by using broad and unambiguous language such as ‘by any and every means whatsoever’, depicted that the original intent was to grant assignees exclusive rights to use and broadcast the works without any restriction. Justice Manish Pitale emphasized the use of such broad terms represented that the assignment was executed ‘in perpetuity’, allowing the plaintiffs to use the song forever; it cannot be limited by changes in technology. The continued acceptance of royalty payments further confirmed assignee’s broad rights However, the Court’s ruling is based on terms of this particular agreement and is not a precedent for all legacy contracts.

Broader Implications of the Judgment:

The Bombay HC’s ruling has far-reaching implications for parties bound by the age-old contracts in the digital era. While the immediate objective was to preserve the efficacy of contractual agreements and assure legal certainty for copyright assignments, its larger impact extends beyond its original purpose.

A significant positive impact of this ruling is that it provides clarity for stakeholders involved, that old, unambiguous contracts can remain enforceable in the digital era. Perpetual assignments provide constant monetization to the assignee without any significant re-renegotiations, furthering business continuity for them. The Court sets a significant precedent that if the assignor accepts royalties, it indicates contracts enforceability. It lays down that subsequent conduct of the parties will be taken into account to stipulate validity of the contract.

While the ruling brings certainty in copyright assignments, it may lead to several long-term adverse impacts for authors/ owners. Firstly, the original creators would be permanently deprived of the revenue generated from their works’ exploitation via new technologies/ mediums. This ruling inadvertently risks promoting the structural imbalance created by the contracts signed in an entirely different context.

This case exemplifies a recent trend of ‘contract fossilization’ where long-standing copyright contracts remain valid despite them being outdated or having become lopsided in favour of one party. Courts often tend to honour the sanctity of the contract; however, it may lead to unfair outcomes for creators who risk losing commercial revenue for their works due to contracts drafted in a complete different context.

Why Should Creators Regain Control Over Assigned Rights?

This judgment reignites the debate: should India like some other countries, allow reversion rights to creators after a certain period of time? The main issue here is regarding the principle of fairness, the authors, while assigning rights, could not have foreseen the future commercial value of their work, giving creators right to renegotiate isn’t undoing the original contract, it’s about adjusting them in the modern context. While the Section-19 (5) of the Indian Copyright Act limits unspecified assignments to 5 years, it was specifically not invoked in this case as the assignment clearly mentioned the ‘in perpetuity’ nature of the agreement which covered all forms of exploitation.

Assignments confer ownership. However, the Indian IP framework doesn’t allow any renegotiation rights for assignments which are broad and unambiguous in nature but as seen in other jurisdictions such as Section-203 of the Copyright Act in the USA that allow authors to terminate agreements and licenses after a period of 35 years. This Section acts as a safeguard for creators who could not have foreseen the future commercial value of their work in a fast changing technological landscape. For instance, the ruling in the case of Lil’ Joe Records Inc. v. Ross et al. underscores that section-203 can be used by authors to terminate long-term contracts. In this case the Florida federal court allowed artists to terminate a 1990 agreement in 2020. The artists opted for termination, as they felt the need to renegotiate in light of the new digital exploitation methods used by the assignees.

What Should be India’s Approach?

This post argues for a policy shift rather than a reinterpretation of contracts by courts. Judicial enforcement of legal agreements are necessary for maintaining certainty, it exposes a structural imbalance where original creators are permanently denied the revenue generated from their own works. The author advocates for a legislative intervention which introduces renegotiation or reversion rights in specific situations such as newer forms of digital exploitation that were never contemplated in the original contract. Such a legislative change would not invalidate the original contract but would offer a chance to creators to renegotiate the terms specifically related to new and unforeseen methods of exploitation thereby, balancing contractual obligation with the artist’s rights.

Conclusion:

This judgment reaffirms how the Indian courts tend to uphold the sanctity of legal agreements, provided they were clear, broad and unambiguous. Though this approach provides legal conviction to stakeholders, it represents a growing gap between pre-modern era contracts and developing technologies. The courts continuing to enforce age-old contracts by interpreting broad contractual terms signed in a completely different context is causing significant loss to artists and their heirs despite their works being exploited in newer ways.

This enforcement of pre- modern era contracts leads to a situation of contract fossilization, India needs to revaluate its copyright regime by including processes such as renegotiation rights of outdated agreements, as seen in the USA. As the digital landscape continues to evolve, the Indian legal system must ensure that its legal framework not only protects contractual sanctity but also takes into account the economic interests of the creators.

[ad_2]

Source link