*Mohit, Rachana, Satej, Shauryaveer, Diya

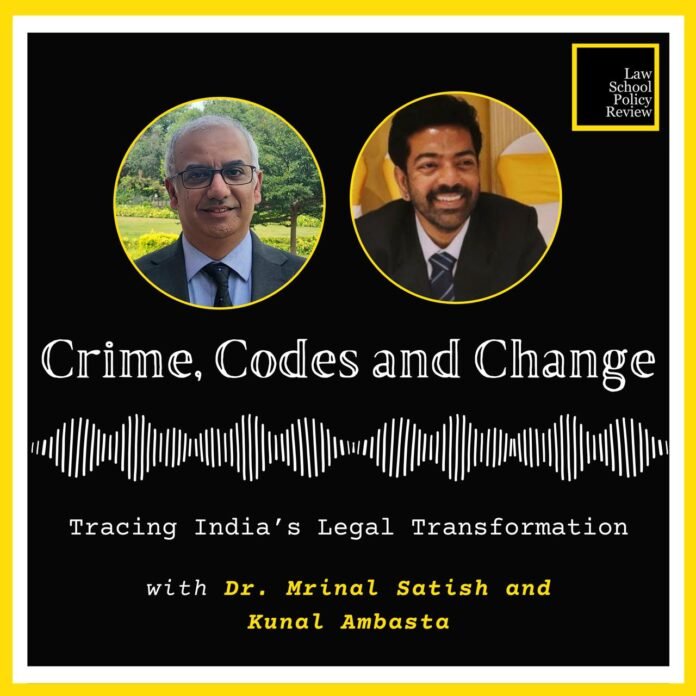

This podcast episode, hosted by Mohit, Rachana, Satej, Shauryaveer, and Diya from the Law School Policy Review (LSPR), features an in-depth discussion on the recent overhaul of India’s criminal law codes. Professors Mrinal Satish (Professor of Law & Dean – Research, NLSIU) and Kunal Ambasta (Assistant Professor of Law, NLSIU) join the panel to critically analyze key provisions of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), and Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam (BSA). Drawing on their extensive expertise in criminal justice and law reform, the guests unpack concerns around anticipatory bail, handcuffing, FIR registration, evidentiary rights, anti-terror provisions, and the impact on marginalized communities, particularly gender and sexual minorities. Through rigorous dialogue, the conversation highlights constitutional tensions, procedural regressions, and missed opportunities for meaningful reform.

This conversation will explore the jurisprudence on conditional consent, its real-world implications, and the role of legal and non-legal remedies. We will also discuss how concepts of justice, sexual agency, and consent vary across legal systems, cultures, and individual experiences.

Theme: A review of the new criminal codes, and an evaluation of the legal reform that has occurred with them.

Participants:

- Interviewers: Mohit, Rachana, Satej, Shauryaveer, Diya

- Guests: Professor Mrinal Satish and Professor Kunal Ambasta

- Technical Support: Aastha

We are glad to host Dr. Mrinal Satish, who is the Professor of Law & Dean – Research at NLSIU, specialising in criminal law with extensive experience in law reform, having assisted the Justice Verma Committee and served as former Chairperson of the Delhi Judicial Academy and Professor Kunal Ambasta, who is an Assistant Professor of Law at NLSIU, teaching criminal law and evidence, with research interests in the criminal justice system and the interface between law, sexuality, and gender identity. On our side from LSPR, we have Mohit, Rachana, Satej, Shauryaveer, Diya as the hosts, and Aastha, who will be helping us out with technical work.

Mohit: First of all, thank you very much professors, for taking some time out of your busy schedules to do this.

The theme today is a discussion of the new criminal laws. There’s a lot that has already been discussed and written about them, but we have culled out the grey areas for what we hope will be a fruitful discussion.

Discussion on the Anticipatory Bail Tests’ Codification

So, my first question to you starts with the legislation on bail. In bail, we have the concept of anticipatory bail under Section 482 of the BNSS, which is a preemptive measure for protection.

Under the CrPC, the court would have used the nature, gravity of the crime, and the criminal history of the accused to decide the question of anticipatory bail. But we see that in the BNSS, there has been a change, and they have incorporated the traditional triple test, which was basically an invention by the court in Siddharam Satlingappa Mhetre v. State of Maharashtra, (2011) 1 SCC 694, not codified in the earlier code. However, post-codification, they have done away with the requirement of considering criminal history and gravity of crime. Therefore, can it be said that the new law is more considerate of the rights of the accused?

Professor Mrinal Satish: I differ from the suggestion that it helps in furthering the rights of the accused for the reason that these provisions, although one could argue that they were vague and gave a lot of discretion to courts in deciding bail applications, the question then becomes: are these the only conditions that the court should bear in mind? By putting these conditions into the statute, we may actually be limiting the court’s discretion rather than expanding it, which is what we are seeing in cases arising from the CrPC provisions.

Professor Kunal Ambasta: Anticipatory bail, as it is understood in its jurisprudential context, is meant to be a discretionary power of the court exercised in each case. And therefore, I agree with what Professor Satish is saying – that codifying all conditions and putting them in the statute may actually limit the process and restrict the discretion that courts would have otherwise continued to exercise. And if you see the ground realities in India, then this becomes very important. So, I don’t think we can say that this is necessarily pro-accused or pro-applicant.

Mohit: A follow-up – We have repeatedly seen that the Supreme Court keeps reiterating “bail is the rule, jail is the exception,” and they have interpreted this under the special laws as well. Why is there a need for such reiteration? What necessitates this? What’s the major flaw that you think is seen as the reason to do this?

Professor Mrinal Satish: The law and judicial understanding – whether it’s CrPC provisions or whatever name it may be called – is premised on the understanding that detention should ensure the accused’s availability for trial, and you ensure that through their presence in court. The basic principle across the world is that detention should be used as a last resort, which is why all of these conditions that have developed are very stringent. So, about passport surrender, bond, surety, as it has been articulated by scholars and by the Law Commission and other commissions, the understanding is primarily based on assumptions about whether the accused will abscond or not, and these assumptions are often flawed. Therefore, this basic understanding that we have of how people will behave is problematic in terms of how we determine their availability for trial.

And again, the big problem is that a lot of people are unable to meet these conditions, which is why they might be granted bail, but they’re still languishing in Indian prisons.

The second issue is with serious offenses. For many serious offenses, the question is whether you actually need to keep someone in custody. One concern is intimidating witnesses – if your understanding is that this person will intimidate witnesses, then you want to keep them in prison. But logically, what we’ve done is that we’ve taken multiple factors and tried to assess one person based on assumptions we cannot actually verify. We’re not talking about what people could actually do, but what we think these people would do based on factors like whether they have property, which is where the entire question of social standing comes in. The assumption is that bail will work for this person because of their social standing.

Then, the question is, although the BNSS has retained these provisions, what are the flaws in the CrPC that have led to this situation? Thus, there is a need for the entire concept to be reconsidered, which the BNSS has not done – it simply takes the CrPC provisions and reiterates them in the same way. So I don’t think we see much movement in terms of major reform.

Professor Kunal Ambasta: Yeah, absolutely. it’s mostly a reiteration. The irony of bail law in India is that though you see judicial pronouncements where courts keep reiterating that marginalized people should be released on bail under far less strict conditions than you might require otherwise, the actual practice is the opposite. The more marginalized you might be – migrant workers, laborers, who do not possess permanent property or immovable property in the jurisdiction of the court, do not have permanent jobs, cannot find people to stand surety for them because they are new to the area, they don’t belong to that particular area – the more difficult it is for you to actually secure bail.

And it’s a lethal combination of many factors. if the seriousness of the crime increases and the accused is also a person who is finding it extremely difficult to get surety or provide property, then it becomes very difficult to get bail. And as Professor Satish was saying, courts make this assumption that the person will abscond, which often results in not granting bail or imposing conditions that they cannot meet. Prison statistics will show you that prisons are full of undertrials. Not all of them are flight risks, but several of them are quite unable to meet the conditions, and therefore unable to secure bail or provide sureties. So, it’s really very ironic.

Justice Krishna Iyer has stated, and he also talked about how people are penalized for their class. He particularly mentioned migrant laborers and migrant workers, and that is exactly what has happened. And knowing that these problems have existed regarding the inability to get bail for thousands of people, the BNSS has not only failed to make an aggressive reform attempt at this very real problem; instead, it has reiterated the provisions of the CrPC, which are the most problematic ones.

Professor Mrinal Satish: Just to add one more point – one of the positive aspects that has been talked about is that the surety amount has been reduced from one-half to one-third, and that will be seen as positive. But again, if you look at Section 479, subsection 2, it says that this reduction applies only if this is the sole offense for the person to become eligible for reduced surety. Now, it also says that if there are multiple offenses, then making it half or one-third makes no difference, because in a lot of these cases, the person is not facing only one offense – multiple cases will ensure that the person never gets bail under this reduced surety provision.

Discussion on Handcuffing Provisions

Rachana: Under the CrPC, handcuffing a person required specific judicial permission. And the case of Citizens for Democracy v. State of Assam went a step further, saying that without judicial sanction, if someone is handcuffed when it doesn’t seem warranted, it will, in fact, attract contempt of court. However, under Section 43(3) of the BNSS, police officers are allowed to unilaterally decide to handcuff an accused person based on things like nature of the offense and likelihood of escape, and it eliminates the requirement for prior court approval altogether. This shift is in contradiction to Supreme Court rulings in cases like Prem Shankar Shukla, which held that routine handcuffing is a violation of Article 21 and human dignity.

So, how do we make sense of this sharp departure from established jurisprudence on handcuffing specifically?

Professor Kunal Ambasta: You pointed out Section 43. What’s very interesting in Section 43 is that you see certain classes of offenders or accused persons that are mentioned. And you see that there is the habitual offender, a person who has escaped from custody, who has committed offences relating to organized crime, terrorist acts, drug-related crimes, illegal possession of arms and ammunition, causing grievous hurt, acid attacks etc. I have a larger point and a specific point about this.

If you see older statutes as well, where, a public servant could cause the death of a person who is resisting arrest. You had provisions such as this in older statutes too. The idea was that there was a rational connection between, let’s say, a person who might resist arrest with such force, particularly in cases where a person knows that they are going to get convicted and sentenced to death. So that person could resist arrest or attempt to resist arrest by force. And therefore, the power extended to law enforcement could also be understood as having a rational connection.

But what is happening here, is that generally, even in the criminal justice system, there is a regression that can be seen, particularly when it comes to the rights of the accused and also how accused persons are viewed. And this is seen everywhere, even in extra-legal actions such as demolitions of houses and property just because an allegation has been made or an FIR has been registered. The approach is moving towards looking at accused persons only through the lens of the crime that they might have committed. And this is an example of a provision which comes from such a mindset.

You rightly pointed out that the precedents on this have been laid down, and the Supreme Court has repeatedly said that routine handcuffing should not be done. And yet you see a provision such as this based on the subjective satisfaction of the police officer as to whether this is necessary or not. Essentially, this reflects how the law is now viewing the accused. The accused is viewed as someone who has committed rape, murder, etc., and therefore deserves this kind of treatment. The larger point is that we need to have a very honest conversation about how we view the rights of accused persons in this country under our Constitution.

The older judgments where Justice Krishna Iyer was talking about keeping people in chains in the Sunil Batra prison cases were very emphatic enunciations of the rights related to dignity and life. These are constitutional rights. We have come a long way from something like that to now talking about accused persons in this way – that you can treat them in this particular manner. And it’s symptomatic of the kind of system that we are inhabiting.

Professor Mrinal Satish: To add to that – if we consider the existing case law, then how would something like this survive? But if you were to ask how it would survive a constitutional challenge, courts might take the approach of trying to balance the rights of the accused against other considerations. Going back to what we just discussed about why we need to detain people in custody – it’s interesting to see how some of these provisions might survive constitutional scrutiny, because on one hand, you have strong constitutional foundations established by precedent. On the other hand, you may have courts justifying the need for some of these measures. It’s not that the police, even under the previous law, did not have power – police officers did have the right to use force that would be necessary to effect an arrest of a person who was resisting arrest.

Professor Kunal Ambasta: Why is this provision even required, and why is this being codified? And if one looks at the categories of offenses now, Section 43(4[1] ) still maintains that rational connection – nothing in this section gives the right to cause the death of a person who is not accused of an offense punishable by death. So that constitutional limitation still exists.

But look at the category of habitual or repeat offenders. For a repeat offender, the provision does not require that the offense be something very serious. So, there’s no gradation or consideration of the scale of offenses, which seems to lack rational connection. Hence, my concern is about the breadth of this provision.

Discussion on FIR Registration and Preliminary Inquiry

Diya: The provision under Section 173 of the BNSS allows for certain categories of offenses which are punishable with imprisonment of three to seven years for a police officer to conduct a preliminary inquiry to ascertain whether there’s a prima facie case that’s worthy of investigation. Now my question is, how does this interact with the Lalita Kumari decision?

Professor Mrinal Satish: One of the justifications for this provision was the criticism that the criminal justice system can provide avenues for misuse. My argument is that it’s actually not addressing that concern effectively. While the provisions have been put in place with good intentions, what emerges more starkly is that despite whatever criticism there may be of the Lalita Kumari case, there were only five specific categories where preliminary inquiry before registering FIR was permissible. This is not a case where a huge set of offenses allows for preliminary inquiry.

But now the police officer has discretion to conduct a preliminary inquiry for a much broader range. I am concerned about the evidentiary value and the potential loss of evidence that you can collect from a crime scene. If you have lost that initial critical period of not being able to collect evidence in the initial few days, and decide two weeks later that this is a case worthy of registering an FIR, then valuable evidence may be lost. what it ends up doing is making it more difficult for people to access the criminal justice system and see that as a big problem.

Professor Kunal Ambasta: If you look at the Lalita Kumari decision, the vast majority of that judgment clearly states that if it is a cognizable offense, then the police has no discretion in the matter. They are bound to register the FIR upon receiving information that discloses the commission of a cognizable offense. It’s only at the end that a narrow exception is carved out for those specific types of cases in which preliminary inquiry can be conducted.

So actually, Lalita Kumari must be read as the Supreme Court being very cognizant of the fact – even from the facts of that case – that for a common person or a victim of a crime, or the victim’s family, getting an FIR registered is a very uphill task. Practically speaking, in this country, the police do not want to register FIRs. They will send you away. They will tell you that this is not the correct jurisdiction or ask you to go somewhere else. And courts have realized this, and Lalita Kumari is an example of the court saying you can’t do this. You must register the FIR, and if we’re talking about victims’ rights, then this new provision is a step back, because now the victim or the informant is left at the mercy of the police.

So there is an offence that is committed, and we know that there are lots of reasons for the police to refuse to register FIRs – it creates a lot of work for them. Once an FIR is registered, it has to reach a logical conclusion. So where will the victims go now? Those cases will often end up being stuck in preliminary inquiries. Is there adequate oversight as to what happens after the police conduct the preliminary inquiry? In particular, if the police conclude that the preliminary inquiry shows it did not warrant registration of an FIR and refuse to register it, where do victims go?

This opens up numerous problems in an area which is already problematic for victims trying to get FIRs registered in this country, and this provision hasn’t been thought through very well.

Furthermore, three to seven years is a very large range. There are offences of many different kinds that can fall within that range. On one hand, you are saying that any repeat offender can be handcuffed and treated in a certain way, and on the other hand, you’re saying that for the entire range of three to seven-year offences, a preliminary inquiry can be conducted. Again, I’m simply unable to understand the rationale for this kind of provision.

Discussion on Section 377 and Gender/Sexual Minorities

Shauryaveer: The BNS removes Section 377 IPC and does not expand rape laws to protect male and trans survivors of sexual assault, creating a legal vacuum for non-peno-vaginal sexual violence. Simultaneously, Section 69 BNS seemingly expands conditional consent beyond promise to marry and introduces vague criteria on identity concealment that could be weaponized against gender and sexual minorities. How does the BNS create legal vulnerabilities for individuals existing beyond heteronormative identities?

Professor Kunal Ambasta: There are two questions there, let’s break it down.

On Section 377, yes, it’s absolutely bizarre that this decision was taken after Navtej Johar in 2018, which had read down 377 to exclude from its ambit consensual sex between adults in private. And what was needed essentially, or would have been much better, was something like an explanation to 377 or an amendment to 377 saying that consensual intercourse would not be covered, but non-consensual intercourse would still be covered, and perhaps the language would have been modernised. We don’t want to use ‘carnal intercourse against the order of nature’ which can mean a lot of things and nothing at all.

The point is that what this shows me is a lack of consideration. This point after 2018 had become so clear. It was so widely reported. People wrote about it, and everyone knew about this, but the fact that you can go through an entire process of re-codification of the IPC, and not even know that these things have happened regarding 377, and therefore the proper thing to do would be to amend it or to add explanations to it, just shows to me how inconsiderate this process was to the rights of sexual and gender minorities. We have now come full circle from protesting and asking for the removal and reading down of 377. Now we are in the situation that we are asking for some kind of penal protection which is no longer there.

It also connects to the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, which had a very important penal provision for assault of trans people. But the positive aspect of that statute was its inclusive language, which specified that its provisions would apply alongside any other criminal penalties found in different statutes. Section 377 could be read along with that. Now it’s gone; you don’t really have anything left.

The last point is, if you saw the recent judgment of Gorakhnath v State of Chhattisgarh by the Chhattisgarh High Court; the High Court seems to equate the marital rape exception from 376 to 377 and say that 377 will also not apply between married couples. different courts have argued that 377 continued to be a protection for married women who were subjected to non-consensual sexual intercourse, which was not peno-vaginal in nature, but now with 377 gone, you don’t even have that protection. So it’s not just the LGBTQ community that suffers because of this, but also married women who can now be subjected to sexual assault of different kinds, all beyond the scope of 376.

Professor Mrinal Satish: There’s also a loss of nuance in understanding what is consent and what you are criminalizing. You create a gap in the law, rather than doing what the Supreme Court suggested – rather than following what the Supreme Court decision indicated.

Professor Kunal Ambasta: On Section 69, there’s a curious questionas to what was the need to introduce this provision. Because rape on the promise of marriage or false promise to marry as offenses under the IPC has been articulated by courts for a long time. This was already covered, so you didn’t need a new offense specifically drafted for that.

And Section 69 provides a very problematic articulation of consent. This approach to promise to marry cases is not right because this is an understanding of consent to a penetrative act, but the consent is vitiated on the basis of deception. If the consent is vitiated, then it should amount to rape. the previous understanding under the IPC was that if the consent was obtained through deception, it did not amount to rape because the fact that your understanding was that there was consent to the sexual act. what we’ve done now is created a separate subcategory of rape, but these are cases of lack of consent, which is similar to what happens between same-sex individuals in relationships. you’re saying this does not amount to rape, but this sort of sexual act is something that you want to criminalize.Section 69 does the same thing by saying this is something different from rape.

Professor Mrinal Satish: when you talk about rape by deception, and if you dwell on that, you have all the traditional problems that come with that concept. Now, will you bring all of those problems into this provision as well?

Professor Kunal Ambasta: The other thing that is happening is regarding the sentencing. In cases of rape, under the main rape provision, the minimum sentence has been increased from seven years to ten years, whereas this provision has a much lower punishment. We need to see whether that differential treatment is justified.

Discussion on Section 106 — Medical Negligence

Satej: On the BNS, we have a question regarding Section 106. Section 106 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita prescribes the punishment for causing death by rash or negligent acts. Although the general term of imprisonment extends to 5 years for anyone convicted under the section, Section 106 carves out a lower maximum term of two years for doctors guilty of negligence in the course of performing medical procedures. How is one to make sense of such differential class treatment being meted out to doctors? Should it be done? Apart from constitutional issues about this, does Section 106 represent a missed opportunity to legislate about rashness and negligence otherwise too?

Professor Kunal Ambasta: So the imprisonment that is mandated for everyone is five years. However, for medical professionals in the course of doing procedures in their practice, if they are negligent, the term seems to have been reduced to two years instead of five. So I have two connected questions regarding this. First is, how do we make sense of such differential treatment meted out to the class of medical professionals, particularly? And apart from the constitutional aspects, the second question is: Is Section 106 a missed opportunity, in some sense, to legislate more closely, more accurately with regards to rashness and negligence standards generally?

If you look at the Indian jurisprudence earlier on, the question of medical negligence – how the court had evolved was very clearly that it has to be gross negligence. And so while reading Section 106, it’s not technically using the word “gross” in the context of medical negligence, but it’s in proximity to the situation under gross negligence. And in other situations, other people have a prospect of a very high level of negligence. So which is why I said, instead of getting a clear definition of that standard, are we getting rid of that word? In this position, you’re not getting rid of it, but you’re creating a distinction. And then, of course, in medical cases, you need a three-member expert committee. Anybody else like us in such diverse sectors – in other cases – you can’t make that sort of characterization.

So there are other, more broadly conceptual questions. I think if you look at Section 304A of the IPC itself, it’s quite outdated. So the term “rash” that we use in Section 304A is not used anywhere else in the homicide provisions. You have a different culpability standard that gets used, which is then interpreted by courts – the exact test of the safety and exercise. And again, there’s quite a bit written on this, saying that it creates confusion in the categories of homicide. What’s the difference between what was Section 300 of the IPC, which seems to be a high level of culpability, Section 299 with respect to knowledge of the fact that the act is likely to cause death, and what was Section 304A in terms of classes? Where does Section 304A fit in the continuum that you have?

Here was an opportunity to clarify and to see whether your negligence causing death – culpable homicide not amounting to murder – where does it fit in your homicide spectrum? we could have considered that, but what we did instead was focus again on increasing punishment rather than looking at the conceptual clarity and discussing the real context. I don’t think these laws really address the conceptual issues.

Professor Mrinal Satish: Absolutely. I think that this is a very rich area of criminal law theory as to what is negligence as something that gives rise to moral culpability deserving of criminal punishment, and it has been worked on for many years across jurisdictions. if you look at Professor H.L.A. Hart’s work on criminal responsibility, he is also talking about what is it about negligence that can justify the imposition of criminal sanction, which requires fault, and it’s not the same as civil damages or sanctions of that kind – it’s qualitatively different.

Indian courts have also relied on the Adomako case in the UK, looking at this question of gross negligence, particularly the case of R v Adomako, which actually deals with gross negligence in a very interesting and detailed way. I think what Professor Ambasta is saying is that this was a good opportunity to incorporate specifically what that standard of gross negligence would be.

Now, I personally feel that the Indian Supreme Court in cases such as Suresh Gupta has got slightly confused between the standards of recklessness and gross negligence. Recklessness requires subjective knowledge, as Professor Ambasta was saying, and involves a psychological state. Gross negligence, on the other hand, is obviously far less culpable and carries far more lenient punishment. And there is a clear distinction between gross negligence and recklessness. If one looks at the judicial trends in India now, this was a very nice and good opportunity. And it’s not a controversial issue – it’s quite well-established in case law coming up to solve this problem and to say that gross negligence will be defined by XYZ standard.

Instead, the focus is only on creating this differential punishment, which also does not make too much sense. It cannot be justified. And you already touched upon that in your question when you talk about the differential punishment for doctors and different punishment for drivers, etc. So, yeah, I think theoretically, this debate is not even looked at by the new structure, and it’s a missed opportunity.

Professor Kunal Ambasta: To add to that, the issue is, if we remove the word “gross” in the subject matter, then my argument would be that the language is very clear, that there’s no need to read “gross” anymore. Then the standard goes back to simple negligence, which is problematic.

Discussion on Section 113 – Definition of a Terrorist Act

Rachana: Section 113 of the BNS, which is identical to Section 15 of the UAPA, which defines a terrorist act. It strips away the protections that the UAPA had provided, which is review by an independent committee, and it leaves the decision of whether to prosecute someone – who could essentially be prosecuted under the UAPA or the BNS at the same time – to a Superintendent of Police at the end of the day.

I have two questions related to this. First, what is the constitutional implication of this sort of differential treatment for people who are essentially committing the same crime at the end of the day? Second, would you agree that the BNS is bringing in these special criminal law provisions and then incorporating them within the general body of the Criminal Code, and in ways that were unknown before. These special criminal laws are becoming normalized – they’re just blended within the general criminal code while stripping away key safeguards.

Professor Mrinal Satish: Section 113, as you pointed out, is identical to Section 15 of UAPA, which is a special statute – the latest iteration of anti-terror law, following a long line of similar statutes. there are lots of questions that arise because of this provision. one can also look at it in a slightly different way, or a long-term view, which is that I think special criminal laws encapsulated in special statutes have essentially been the gateway or legal mechanism to normalize procedures into law that are otherwise deviations from fundamental principles. And this has occurred to various extents in different contexts.

There was a time when police confessions made to police officers, etc., were also covered under some special laws. The law has moved on from that, but procedurally, these special laws have always been tilted to the detriment of the accused. And what is now happening with provisions such as Section 113 is a collapse of the distinction between Special Criminal Law and the general criminal law.

The really interesting question that arises is: What would remain in your general principles? What would remain in your general code of criminal law if everything mirrors the special law, and procedurally you can choose between them? I find this discretion at the end very interesting, because what exactly is the officer choosing? The Superintendent if Police is choosing which procedure will best suit the ends of whatever is in his mind, right? And it’s really interesting that you’re creating options such as this, even when you have UAPA available.

This brings me to the point about the question of sanctions. UAPA also has some kind of safeguard in terms of sanction requirements. And if you look at it, a lot of UAPA cases end in acquittals because the sanction is improper. You have a lot of cases under this particular statute, under this provision, and again, it’s about procedural fairness. Now you’re changing the sanction requirement there.

What I mean is, suppose that your sanction is deficient under UAPA. Will you use Section 113 to avoid an acquittal under UAPA? Something like this should not fairly occur.

The second thing is this: I would still be okay with this if, let’s say, you said that now that we have something like Section 113, we don’t need UAPA anymore – let’s repeal UAPA – because the general law can now deal with terrorism. This has been the justification that has been given to us for years, saying that the general law cannot deal with the special threat of terrorism, which has offenses that are very difficult to detect which are very difficult to prosecute. Not that special laws have been successful in prosecution – if you look at the conviction rates, they have been abysmally low.

So if general laws are rising up to the challenge, can we do away with UAPA? That’s the question. But I don’t think that will happen.

Professor Kunal Ambasta: One more thing would be the question of whether this serves all the purposes that it’s supposed to serve. That’s not really defined as a routine safeguard, but I think that brings us back to questions of differential treatment and doing away with the safeguards, which creates definitional problems. The concepts that they have defined need better conceptual definition.

Professor Mrinal Satish: There have been cases in the past where a person has been tried under the special law and also under the IPC, and the procedure under the special law is being used. There have been cases where the the accused has been discharged or acquitted of the special offence. So then a very interesting question arises, which has been answered by the Supreme Court, but I think still is a live question: What happens to, let’s say, evidence that could have been only admissible under the special law? Should it be used now for the IPC offences?

The Court has said yes, but it was still a live question in some sense. Now, of course, there is no difference, because terrorism is also in the BNS.

Discussion on Section 30 of the IEA — Right to Confront Co-Accused

Mohit: The last question that we have today is about confessions. In the past, confessions made to the police could be used against co-accused, but the admission of such evidence was hedged in by the safeguard of joint trial under Section 30 of the Indian Evidence Act. This allowed the accused to confront his co-accused. However, the new BSA introduces an explanation, and what this explanation does is deem a joint trial even when the co-accused has absconded. So, what implications do you think this will have? And do you think that this is a sort of in absentia form of trial there?

Professor Mrinal Satish: That’s an interesting question, but there is one thing that I would just like to clarify. It was not that confessions were always made to the police, because under the Indian Evidence Act, confessions made to police officers are inadmissible. Section 30 of the Indian Evidence Act, which has been retained, specifically required that the confession should be judicial, which automatically meant that it was a confession made before a magistrate, not to the police.

But your question is very interesting. So this requires at least two accused, because there has to be a confession. If there are two accused, the first accused’s confession implicates himself and also implicates the second, right? It is not that the blame is being shifted entirely on him. The same person is implicating himself. He confesses to his own involvement, and then there was a very interesting safeguard there, which you pointed out – that it must be a joint trial.

The reason for that was that in a joint trial, if my confession is being used against my co-accused, he gets a chance of pointing out any inconsistencies with that confession. If I am asked to come and prove my confession by reading it out, he gets a chance to cross-examine me. Now these might seem very ordinary procedural rights, but they are fundamental to a fair trial. This is what ensures that an accused gets a fair trial – the right to confront the evidence against that person.

Here, Explanation 2 to Section 30 is very problematic, because it says that this confession can now be taken into consideration in absentia. Now, there are two things that can arise. One is, let’s say my confession is being used against me, and I have run away, I have absconded – it’s my fault. I take upon myself the forfeiture of my rights by absconding.

But let’s say I have absconded, and the confession is being used against my co-accused. Now he is not getting a chance to cross-examine me. He is not getting a chance to question that confession, even though he has not absconded. My cross-examination might have revealed, which could have been a three-month-long cross-examination, and all those safeguards are now lost. Something might have come out in that cross-examination that could cast doubt on my confession. So he loses the right to a fair trial for no fault of his. He has not absconded; he is facing the trial.

In fact, this might incentivize the prosecution to ensure that one accused absconds after giving a very nice, very detailed confession, and then becomes a small fry in the larger conspiracy. The prosecution was never really after him anyway. The person the prosecution wanted convicted was the co-accused. So now it’s a big problem for the co-accused.

There is one last thing here, which is that such a confession is anyway of very low evidential value. The Supreme Court has said in Kashmira Singh and other cases that it can be considered only after all the other evidence has been considered. That’s the only saving grace, but on a criminal fairness point, this explanation makes no sense.

Mohit: Due to the paucity of time, I think we’ll have to end it here. Thank you very much, Professors, this was a very fruitful session for us, and I hope for the audience as well. Thank you for your time and knowledge, Professors.

Professor Mrinal Satish: Thank you, thanks so much for the session and thanks for inviting us.

Professor Kunal Ambasta: Thank you so much. This was a good session.