[ad_1]

Allegations of cruelty in divorce case should be specifically challenged in cross examination

Now, given that

“4. The only point urged albeit strenuously on behalf of the appellant by Mr P.S. Mishra, the learned Senior Counsel is that as there has been no valid service of notice, so all proceedings taken on the assumption of service of notice are illegal and void. He has invited our attention to the judgment of the learned Rent Control Tribunal wherein it is recorded that Exhibit AW 1/6 dated 5-8-1986 was sent by registered post and the same was taken by the postman to the address of the tenant on 6-8-1986, 8-8-1986, 19-8-1986 and 20-8-1986 but on those days the tenant was not available; on 21-8-1986, he met the tenant who refused to receive the notice. This finding remained undisturbed by both the Tribunals as well as the High Court. Learned counsel attacks this finding on the ground that the postman was on leave on those days and submits that the records called for from the post office to prove that fact, were reported as not available. On those facts, submits the learned counsel, it follows that there was no refusal by the tenant and no service of notice. We are afraid we cannot accept these contentions of the learned counsel. In the Court of the Rent Controller, the postman was examined as AW 2. We have gone through his cross-examination. It was not suggested to him that he was not on duty during the period in question and the endorsement “refused” on the envelope was incorrect. In the absence of cross-examination of the postman on this crucial aspect, his statement in the chief examination has been rightly relied upon.

There is an age-old rule that if you dispute the correctness of the statement of a witness you must give him opportunity to explain his statement by drawing his attention to that part of it which is objected to as untrue, otherwise you cannot impeach his credit. In State of U.P. v. Nahar Singh (1998) 3 SCC, a Bench of this Court (to which I was a party) stated the principle that Section 138 of the Evidence Act confers a valuable right to cross-examine a witness tendered in evidence by the opposite party. The scope of that provision is enlarged by Section 146 of Evidence Act by permitting a witness to be questioned, inter alia, to test his veracity. It was observed: (SCC p. 567, para 14) “14. The oft-quoted observation of Lord Herschell, L.C. in Browne v. Dunn [(1893) 6 R 67 (HL)] clearly elucidates the principle underlying those provisions. It reads thus:‘I cannot help saying, that it seems to me to be absolutely essential to the proper conduct of a cause,

where it is intended to suggest that a witness is not speaking the truth on a particular point, to direct his attention to the fact by some questions put in cross-examination showing that that imputation is intended to be made, and not to take his evidence and pass it by as a matter altogether unchallenged, and then, when it is impossible for him to explain, as perhaps he might have been able to do if such questions had been put to him, the circumstances which, it is suggested, indicate that the story he tells ought not to be believed, to argue that he is a witness unworthy of credit. My Lords, I have always understood that if you intend to impeach a witness, you are bound, whilst he is in the box, to give an opportunity of making any explanation which is open to him; and, as it seems to me, that is not only a rule of professional practice in the conduct of a case, but it is essential to fair play and fair dealing with witnesses.’ (emphasis supplied)[Para No.11]

Although the appellant, in the grounds adopted in the appeal, has assailed the reliance of the learned Family Court on the decision in State of U.P. v. Nahar Singh (1998) 3 SCC 561 to contend that the same was a criminal case and the precedent arising therefrom could not apply to cross examinations in matrimonial proceedings, which are civil proceedings by nature, there is no merit to this opposition; especially in the light of the observations of the Supreme Court in Darshana Devi’s case which was a civil proceeding. In fact,

When we view this in addition to the fact that

“14. Thus, to the instances illustrative of mental cruelty noted in Samar Ghosh, we could add a few more.

Making unfounded indecent defamatory allegations against the spouse or his or her relatives in the pleadings, filing of complaints or issuing notices or news items which may have adverse impact on the business prospect or the job of the spouse and filing repeated false complaints and cases in the court against the spouse would, in the facts of a case, amount to causing mental cruelty to the other spouse. xxx

22. We need to now see the effect of the above events. In our opinion, the first instance of mental cruelty is seen in the scurrilous, vulgar and defamatory statement made by the respondent-wife in her complaint dated 4/10/1999 addressed to the Superintendent of Police, Women Protection Cell. The statement that the mother of the appellant-husband asked her to sleep with his father is bound to anger him. It is his case that this humiliation of his parents caused great anguish to him. He and his family were traumatized by the false and indecent statement made in the complaint. His grievance appears to us to be justified. This complaint is a part of the record. It is a part of the pleadings. That this statement is false is evident from the evidence of the mother of the respondent-wife, which we have already quoted. This statement cannot be explained away by stating that it was made because the respondent-wife was anxious to go back to the appellant-husband. This is not the way to win the husband back. It is well settled that such statements cause mental cruelty. By sending this complaint the respondent-wife has caused mental cruelty to the appellant- husband.

24. In our opinion, the High Court wrongly held that because the appellant-husband and the respondent-wife did not stay together there is no question of the parties causing cruelty to each other.

Staying together under the same roof is not a pre- condition for mental cruelty. Spouse can cause mental cruelty by his or her conduct even while he or she is not staying under the same roof. In a given case, while staying away, a spouse can cause mental cruelty to the other spouse by sending vulgar and defamatory letters or notices or filing complaints containing indecent allegations or by initiating number of judicial proceedings making the other spouse‟s life miserable. This is what has happened in this case.xxx

28. In the ultimate analysis, we hold that the respondent-wife has caused by her conduct mental cruelty to the appellant- husband and the marriage has irretrievably broken down.” (Emphasis Supplied)[Para No.14]

the DV Act on false grounds was designed to cause him harm and amounted to mental cruelty.

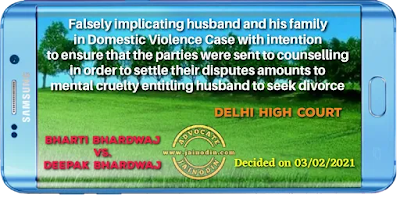

Delhi High Court

Bharti Bhardwaj

Vs.

Deepak Bhardwaj

Decided on 03/02/2021

[ad_2]

Source link