1. Introduction

The decision in Corn Products Refining Co. v. Shangrila Food Products Ltd.[i] remains one of the most pivotal judgments in the field of trademark law. In this case, the Court found that the trademark “Gluvita,” registered by the defendant, was deceptively similar to “Glucovita” which is a mark registered under class 30 named as Dextrose (d-glucose powder mixed with vitamins), and could cause deception or confusion under Sections 8(a) and 10(1) of the Trade Marks Act, 1940.[ii] The ruling emphasized on phonetic similarity, suggesting even minor resemblances could mislead consumers. While the judgment established a key precedent, it has placed overreliance on phonetic similarity, risking monopolization within trademark classes, which is unfavourable from a utilitarian perspective. This post critiques the decision by examining the limitations of the “average intelligence” test used by the Court and advocates for a more balanced and flexible framework in trademark jurisprudence that better reflects consumer behaviour and market dynamics.

2. Critique of Phonetic Similarity as a Primary Criterion in Trademark Infringement Cases

Trademark infringement jurisprudence frequently prioritizes phonetic similarity when determining the likelihood of confusion.[iii] While phonetic resemblance undoubtedly plays a role in consumer perception, excessive reliance on this factor can distort the nuanced analysis required for trademark disputes. The landmark case of Cadila Healthcare Limited v. Cadila Pharmaceuticals Limited exemplifies this issue, as the Delhi High Court initially treated phonetic similarity as a decisive factor in determining infringement. However, this approach was revised by the Supreme Court in 2001, which advocated a factorial method rather than an exclusive focus on phonetics. Consequently, critiquing Cadila using Hoffmann-La Roche v. Cipla[iv] misinterprets the precedent, inadvertently relying on an outdated case to assess a more recent legal framework. This contradiction underscores the need for a more precise understanding of how phonetic similarity should function within broader trademark analysis.

Trademark law seeks to prevent consumer confusion while safeguarding fair competition. Given this objective, evaluating infringement solely based on phonetic similarity disregards other vital elements that shape brand identity. Visual appearance, market positioning, and branding strategies are equally significant in distinguishing one trademark from another. Modern jurisprudence recognizes this necessity, as seen in the Supreme Court’s shift away from phonetic exclusivity in Cadila towards a more comprehensive evaluation.

For instance, the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011, [v] which was reviewed under WTO dispute settlement mechanisms, reinforced that brand differentiation extends beyond phonetics.[vi] The Act mandated uniform packaging for tobacco products, effectively removing visual elements of branding. This led to a WTO challenge, wherein brand owners argued that the Act diluted their trademarks by eliminating their distinctive visual aspects. The WTO’s assessment acknowledged that trademarks are multifaceted, encompassing visual, phonetic, and conceptual elements. This perspective supports the argument that phonetic similarity alone cannot serve as the primary criterion for determining trademark infringement. [vii]

A critical issue in relying on Cadila and Hoffmann-La Roche as guiding precedents for broader trademark disputes is the distinct regulatory environment surrounding pharmaceutical trademarks. The likelihood of confusion standard for pharmaceutical products differs significantly from that of general consumer goods. Public health considerations necessitate heightened scrutiny, as confusion between similar-sounding drug names could have severe consequences. This elevated standard, recognized in Cadila, underscores that pharmaceutical trademark disputes should not be used as general precedents for other industries where consumer risk is lower.

Conversely, the present case pertains to non-pharmaceutical products and follows a different analytical framework. The juxtaposition of these cases raises a fundamental question: should pharmaceutical trademark rulings influence broader trademark jurisprudence? Given the stricter threshold for confusion in the pharmaceutical sector, applying similar principles to general trademark disputes risks conflating distinct legal standards.

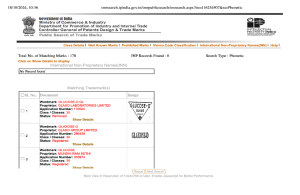

Further, there are questions regarding the fairness of the registry , which are raised since they fail to conduct the basic primary phonetic public search before the acceptance of the marks which clearly showcases that similar marks do exist, such as glucose and glaxose-D(Annexure -A). In Insead v Full stack Education,[viii] the Court directed the registry to conduct both word mark and phonetic searches at the preliminary stage, the manual clearly outlines that a phonetic search is part of the examiner’s duties when assessing the relative grounds for refusal under the rule 33 of the trademarks rules, this showcased, how the act of the ill acts of registry frivolous litigations that simply delay the proceedings of the court.

3. Monopolisation of one class

The impugned judgment of corn products could allow companies to claim exclusive rights over common or generic-sounding words, thereby effectively monopolizing language within certain product categories.[ix] The Section 11(1) of the Trade Marks Act[x], prohibits the registration of a mark that is “identical with or similar to an earlier trademark,” but the Act provides leeway if the coexistence of marks does not cause confusion among consumers. In the case of the Nandhini Deluxe v. Karnataka Cooperative Milk.,[xi] it was seen that similar-sounding trademarks—’Nandhini’ and ‘Nandini’ were allowed to coexist, if the trademarks were visually distinct and used for different products; therein one was for milk and other for a chain of the restaurants, and thus there could not exist a monopoly over one class. Further in the case of Vishnudas Trading v. Vazir Sultan Tobacco Co. Ltd.,[xii] it was stated that it is often seen that there is trademark claim over a broad class; however if the products are significantly different then it should not monopolize all products in that category.

The trademarks, thus, now help in the existence of multiple products rather than act as a barrier to entry.[xiii] By granting companies exclusive rights over similar-sounding words, it helps in co-existence of multiple, particularly smaller or newer companies that may not have the resources to create wholly original or unique brand names.

4. Revisiting the “Average Consumer” Standard

The notion of an “average consumer” with imperfect recollection is inherently flawed,[xiv] due to its vagueness and inability to reflect the wide spectrum of consumer education, socioeconomic backgrounds, and cultural experiences. This assumption of a homogeneous consumer base overlooks the reality that individuals may have varying levels of understanding regarding products like “Glucovita” which are nutritional in nature and their competitors. Courts should refrain from presuming universal confusion among consumers when encountering similar-sounding trademarks. A more nuanced approach is required, considering factors such as the product’s category, price range, and the accessibility of information through digital platforms. In today’s technologically advanced world, consumers of average intelligence are increasingly likely to cross-check product origins and brand specifics using the wealth of information readily available online, thereby minimizing the potential for confusion or deception.[xv] Consumers purchasing a product like “Glucovita”often associated with health, energy supplements, or wellness—are likely to be more discerning and informed than the average consumer in a general market. These consumers tend to have a better understanding of product composition, benefits, and brand identity, making them less susceptible to confusion by similar-sounding trademarks. They may also rely on product-specific research or recommendations, further reducing the likelihood of deception. Therefore, applying a general standard of “average intelligence” overlooks the nuanced purchasing behaviour in specialized markets like Glucovita’s.

5. The Need for Trademark Protection

The utilitarian theory in intellectual property law asserts that legal protections should primarily serve to maximize societal welfare by fostering innovation and creativity while ensuring that the benefits of these advancements remain accessible to the public. This philosophy is rooted in the principle of achieving “the greatest good for the greatest number.” Viewed through this lens, the Corn Products judgment raises concerns, as it risks stifling competition and innovation by granting exclusive rights over descriptive or generic terms. [xvi] For instance, allowing trademarks like “Gluco” in Glucovita could monopolize commonly used language, thereby restricting other businesses from effectively communicating essential product attributes. Such monopolization could hinder market competition and limit consumer choice, contradicting the broader objectives of trademark law, which aim to balance brand protection with fair market practices. A more nuanced approach is necessary—one that prevents unjustified monopolies while safeguarding the distinctiveness of genuine trademarks. This balance would ensure that intellectual property laws encourage creativity without impeding fair competition or consumer access to information.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while the Corn Products decision clarifies trademark law, has its flaws. The excessive focus on phonetic similarity, potential for monopolization, and shortcomings of the average consumer test underscore the need for a more nuanced framework. Courts must embrace a holistic approach that promotes competition, innovation, and consumer welfare.

ANNEXURE- A

End Notes

[i] Corn Products Refining v. Shangrila Food Products Ltd, AIR 1960 SC 142.

[ii] Deceptive similarity in trademarks with respect to medicinal products has a threatening effect – a brief overview. IIPRD. https://www.iiprd.com/deceptive-similarity-in-trade-marks-with-respect-to-medicinal-products-has-a-threatening-effect-a-brief-overview/

[iii] Trade Marks Act, 1999 Section 2(1)(h).

[iv]F. Hoffmann-La Roche v Geoffrey Manners AIR 1970 SC 2062

[v] Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011, § 20 (1), (2), (3) (Prohibition on Trade Marks and Marks generally appearing on retail packaging), Panel Report, paras 7.2723, 7.2764, 7.2794, 7.2867-7.2868.

[vi] Shree Nath Heritage Liquor Pvt Ltd. v. Allied Blender & Distillers Pvt Ltd, FAO (OS) 368 and 493/2014.

[vii] Barton Beebe, J. C. F. (2023, March 24). Are we running out of trademarks? an empirical study of trademark depletion and congestion. Harvard Law Review. https://harvardlawreview.org/print/vol-131/are-we-running-out-of-trademarks/

[viii] Insead v Full stack Education. C.O. (COMM.IPD-TM) 1/2021, Order dt. May 17, 2023.

[ix] Barooah, S. P., About The Author Swaraj Paul Barooah ., Kaushal, T., Byadwal, Y., & SpicyIP. (2020, September 4). Guest post: Monopolizing generic terms?. SpicyIP. https://spicyip.com/2014/01/guest-post-monopolizing-generic-terms.html

[x] Trade Marks Act 1999, S.11(1).

[xi] Nandhini Deluxe v. Karnataka Cooperative Milk 2018 SCC ONLINE SC 741.

[xii] Vishnudas Trading v. Vazir Sultan Tobacco Co. Ltd., AIR 1996 SC 2275.

[xiii] N, A. R. (2019, April 9). Similar marks for dissimilar goods in the same class. SC IP. https://www.sc-ip.in/post/similar-marks-for-dissimilar-goods-in-the-same-class

[xiv]Bharadwaj Jaishankar , Jaishankar, B., & Parashar, K. Who is an average consumer with imperfect recollection?. Who Is An Average Consumer With Imperfect Recollection? – Trademark – Intellectual Property – India. https://www.mondaq.com/india/trademark/1156842/who-is-an-average-consumer-with-imperfect-recollection

[xv] The “average consumer test” in an informed society. S.S. Rana & Co. (2024, June 14). https://ssrana.in/articles/the-average-consumer-test-in-an-informed-society/

[xvi] PAUL, RITU, Intellectual Property Rights: A Utilitarian Perspective (May 9, 2021). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3842429 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3842429

About Author: The Author Stuti Mehrotra is a fourth-year BBA LL.B. (Hons.) student at O.P. Jindal Global University, deeply interested in exploring the intersections of intellectual property and consumer rights through critical legal analysis.

Image source: here

[ad_1]

Source link