[ad_1]

Perhaps for the first time, a Hyderabad Court granted an interim injunction application under the PPVFRA. To me, however, the order stands out for all the wrong reasons. The Court, in deciding the injunction, relies solely on the Plaintiff’s in-house laboratory to prima facie decide infringement. It omitted to appoint a scientific expert u/s. 66 of the Act while deciding crucial scientific questions. It further failed to delineate the parameters for deciding an interim injunction application under the PPVFFRA. In my opinion, although a first of its kind, the case is not a strong precedent and is likely to be overturned on appeal.

Claiming Infringement u/s. 64

Advanta alleged that ‘Bharat 756 power’, a hybrid maize variety of the Respondent, was identical to its registered variety ADV 759. It conducted DNA and DUS tests on the respondent’s variety in an in-house laboratory. A DUS test is used to assess whether a variety is novel, distinct, uniform and stable (DUS) compared to existing hybrids u/s. 15 of the PPVFRA. A DNA test, on the other hand, helps to see if two varieties have similar genotypes (genes or genetic makeup).

The reports showed that the genetic makeup, external features, and traits possessed by Bharat 756 were identical to ADV 759. Bharat 756 matched all 31 characteristics and other distinctive features of ADV. Advanta also argued that a variety identical to ADV 759 could not be obtained unless the parental lines registered with the petitioner were crossed. Since the respondent did not disclose which parental varieties it crossed to obtain Bharat 756, they likely crossed the parental lines registered with the petitioner. Thus, the Petitioners argued infringement u/s. 64 and sought an injunction against the Respondent u/s. 66 of the Act.

Independent Creation as Defence? Respondent’s submissions

First, Respondent contended that the hybrid variety ‘Bharat 756’ was independently created and developed by the R&D department of the company.

To me, the argument does not have merit. U/s. 28(1) of PPVFRA, an entity with a certificate of registration, has the exclusive right to “produce, sell, market, distribute, import or export the variety.” Under PPVFRA, independent creation is not a defence to infringement.

Second, it disputed the credibility of test results conducted by the Petitioner on the respondent’s variety (DUS and DNA).

The Petitioner tested both varieties in their in-house laboratory. Under rule 29(7), during the registration process, a DUS test of the variety has to be conducted at a minimum of two locations, which are preferably notified, empanelled institutions. Further, the manner in which the tests are to be performed is to be notified by the PPVFR authority in the ‘Crop Guidelines.’ The guidelines for testing Maize (subject matter in the present case) can be seen here.

The respondent argued that a similar process must be followed while deciding infringement u/s. 64. The process reinforces the credibility and integrity of the results. Relying on the reports produced by the litigant, however, increases the potential of manipulation and distortion.

The Petitioner retorted that neither the PPVFRA nor the rules prescribe any procedure which is required to be followed to prove infringement. The process for DNA and DUS tests u/s. 19 and rule 29(6) is confined to the period before registration. As long as the process followed is scientific, it is acceptable even if it is different from the registration process. Hence, testing at PPVFR-notified labs under Section 19, read with Rule 29(7), was not required.

Tests to be used for Infringement: Ensuring Credibility and Integrity

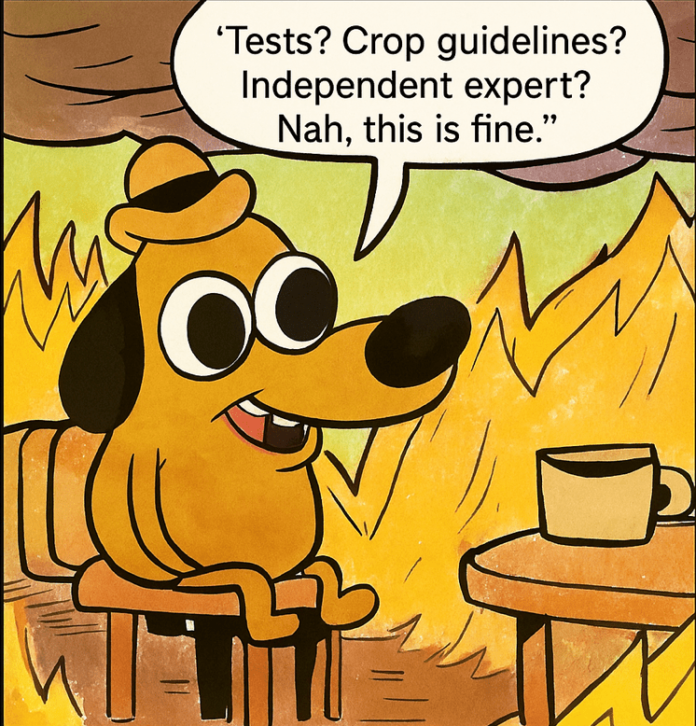

The Court held that as long as the Petitioner followed the procedure for testing before registration, it did not need to follow the same process for infringement. Relying solely on the comparison report of Petitioner’s in-house laboratory, it held that Bharati 756 variety and parental lines are ‘deceptively similar’ to ADV 759.

The Court fails to engage with the arguments that the tests were not conducted in conformity with PPVFRA and the rules. The process followed before registration ensures there is no bias or manipulation in the reports. The tests are conducted at laboratories which are not associated with the applicant. Further, the empanelled institution possesses adequate facilities for conducting DUS or special tests. (rule 29(7)) This ensures that the tests follow acceptable scientific norms. The integrity and credibility of the reports, thus, are presumed.

The Respondent had raised serious concerns around the methodology used by the Petitioner to test the varieties. For instance, it was argued that the Petitioner did not use the genetic markers or labels for Bharat 756 during the testing process. The absence of the markers, it said, rendered the test unreliable and untrustworthy. Further, the Petitioner also did not follow the crop guidelines released by the PPVFR authority since the test was not conducted at a minimum of two places.

I am not arguing that the Act mandates an identical process to prove infringement. An argument of judicial overreach could be made if the Court did that. However, the Court could have said, “Any scientific process used to prove infringement must conform to the same level of integrity and credibility as the process followed during registration.” The onus could be placed on the Defendant to dispute the credibility of the test or the integrity of the process used to obtain the results.

In the present case, the Court brushes aside the valid allegation of lack of credibility against the in-house report. Further, it does not inquire if the process used to obtain the report followed acceptable scientific norms. The Court must ensure that the decision is based on reports which are beyond a reasonable doubt. In my opinion, on balance, the Court made a wrong decision based on a report which, prima facie, has been questioned on a scientific basis.

Failure to Appoint a Scientific Expert

U/s. 67 of PPVFRA, the Court is empowered to appoint an independent scientific advisor to inquire into a fact or scientific issue. In the present matter, since the scientific validity of the Petitioner’s report was in question, the Court could have appointed an independent scientific advisor. The adviser, in turn, could have aided the Court to form an opinion as to whether the test was conducted following scientific rigour or whether the absence of a genetic marker could distort DNA results or whether the process enumerated u/s. 19 r/w rule 29(7) is the best way to ensure credibility. If done this way, the allegations raised by the Respondents could be addressed in a meaningful manner. Instead, the Court chose to brush aside the allegations without any meaningful engagement.

Unexplained Haste in Passing the Order: Seasonal Urgency? Public Interest?

Notably, the Court had appointed an Advocate Commission to collect samples of hybrid varieties from both parties and submit them for testing at the TISTA laboratory. According to submissions, TISTA is an empanelled laboratory, i.e. adequate facilities for conducting DUS and other special tests. As recorded in Para 21, TISTA had requested the Respondent to provide genetic markers of their variety for the purposes of testing. The Respondent, however, did not provide the same and requested the Court for directions to TISTA to maintain the confidentiality of the markers supplied for testing. This resulted in a delay in conducting the tests and preparing of results.

The Court instead relied upon the test results prepared by the Petitioners’ in-house laboratory. A question then arises- Why did the Court refuse to wait for TISTA’s findings on the issue?

One possible reason could be the impending Kharif season. The Petitioner had argued that in case the interim injunction was not granted, the Respondent “will flood the market in the upcoming Kharif season with the infringing variety Bharati 756”. Thus, urgent relief was required.

If the Court did consider seasonal urgency as a relevant factor in deciding the injunction application, it ought to have stated so explicitly. In deciding injunction applications, the Courts must lay down all the factors that weighed in the Court’s mind while deciding the application. Allow me to elaborate.

The Respondent had argued that the Petitioner’s variety was being sold at a higher price compared to the Respondent’s variety. PPVFRA’s statement of objects and reasons states, “ensure the availability of high-quality seeds and planting material to the farmers.” Thus, PPVFRA, intrinsically, has a public interest element, i.e. availability of high-quality seeds and planting material.

Therefore, the Court could have laid down whether ‘public interest’ should be considered in deciding such applications or not. Unfortunately, as pointed out, it is unclear which factors the Court considered relevant while deciding the injunction application.

In my opinion, reading the scheme of PPVFRA, it is important to consider the interests of farmers while deciding injunction applications. The growth of the seed industry and access to high-quality seeds at affordable prices are important objectives of the Act.

[ad_2]

Source link