Namaskar,

I recently read How GN Devy Challenges Our Concept of Knowledge by Martand Kaushik. If you have not heard of him, G. N. Devy is an Indian cultural activist, literary critic, and former professor of English. He is the author of a long list of books and papers, and has been anointed with several awards, including the Sahitya Akademi award, a SAARC Literary Award, the Prince Claus award, the international Linguapax prize, and the Padma Shri.

And yet, as the Martand notes and I concede, “his name can evoke blank stares, even among those within academia.” As someone interested in and researching the relationship between knowledge and power vis-à-vis copyright law, I’ve been reading thinkers like Foucault, Barthes, and Bourdieu for some time. But I hadn’t read Devy. And that absence struck me.

This point clung to my head and got me thinking (and I still am): Does mere access to research and resources suffice to dismantle the deep-rooted epistemic structures? In other words, in a world where access to knowledge is increasingly sought, the question isn’t just who gets to read but also what gets read, and why? Intellectual Property law, especially copyright, is rightly criticised for obstructing access to information and knowledge. And these questions have profound implications for our IP thinking. But there are barriers beyond access, and these are harder to name.

In this short post, I just wanted to share a few personal experiences and intellectual anxieties. They may not be directly about IP, but they shape—and are shaped by—how we describe, frame, and generate knowledge in the field of IP and beyond.

‘P’ for Paris and/or Power …?

As someone who studied in India and is currently studying in the French academic space, I’ve been fortunate to have amazing institutional support—ample access to databases, literature, and the intellectual environment one needs for scholarly growth. And yet, despite (or perhaps because of?) this access, I find myself repeatedly reading and gravitating toward Western thinkers—Foucault, Bourdieu, Barthes, Derrida, to name a few—whose ideas continue to shape my PhD project and many around me. Their ideas are undeniably powerful and empowering. And I don’t question their brilliance. But they also form the intellectual air I (/we) breathe in here. It is seductive, contagious, readily available, and equipped with compelling (English and French) vocabularies to speak of power, knowledge, and the world. This makes me wonder, what happens when particular modes of thinking become default settings? Perhaps it is not just about accessing knowledge but also about unsettling its centres.

My Freedom, My Subjection …

Of course, I’m free to read what I want—my supervisors are wonderfully supportive and encourage me to explore whatever resonates with my research. They highlight wherever I fail to cite and read diversely. And yet, as K.C. Bhattacharya said in his 1931 lecture “Swaraj in Ideas”, this is precisely where power operates: freedom remains the site of subtle subjection. Foucault, of course, unpacked this with sharp brilliance. As Prof. Bhattacharya said,

“When I speak of cultural subjection, I do not mean the assimilation of an alien culture. That assimilation need not be an evil; it may be positively necessary for healthy progress and in any case it does not mean a lapse of freedom. There is cultural subjection only when one’s traditional cast of ideas and sentiments is superseded without comparison or competition by a new cast representing an alien culture which possesses one like a ghost.”

It may be about my (one’s) academic preference why I read someone or a deeper question of epistemic proximity and distance. But being situated in France—culturally, and institutionally—I am enveloped in a system that trains my attention toward the West. The structures here (libraries, syllabi, conferences, even casual intellectual conversations) pull me into that orbit. We speak of Foucault and Derrida as if we speak of rock stars. And even when I feel the limits of these thinkers—their silences on caste, their indifference to colonial legacies—I still return to them. Not because I must, but because the system or the environment around me makes them legible, visible, usable, and legitimate. To put it simply: they come pre-approved. Say Foucault, and you’re speaking the language of theory. Say Devy, and the room goes quiet—not out of reverence, but uncertainty. It’s as if mentioning Adi Śaṅkara (an Indian philosopher from around c. 700 CE) cues a monologue, not a dialogue. You speak with Foucault; you listen to Devy. One sparks debate, the other gets treated like a lecture you did not sign up for, or you just curiously tolerate. Needless to say, both lend tools to question them and the world, wherever needed.

There’s also a strange kind of homesickness involved. Studying abroad can feel like living in two intellectual homes: one that raised us, textured by Indian, Vietnamese, Ghanaian, Ethiopian, or other Global South thought traditions. And the other that now hosts us—Western, institutional, legible. The second comes with recognition, resources, and reach—forms of capital to navigate the field. The first often demands recovery, translation, even defence. And yet, I say, both empower, inhabit, and make us who we are. From where we stand, we can (at least) try to make visible the structures that render Plato “natural” and Maitreyi “distant.” But please don’t discuss or dismiss it as a matter of taste because it’s not so. It’s the power/knowledge structures that (make us) define what counts as “true,” “worthy,” “useful,” and what gets dismissed as “context.”

So … will I stop reading Western scholars after writing this post? Of course not. But it does make me more conscious of my positionalities. Does this signal an epistemic asymmetry? Yes. Does it create an epistemic burden? Maybe yes, maybe no. But it surely adds a sharpened layer of awareness that cannot be unfelt once felt. With the awareness, we might feel like carrying an added responsibility to “correct” the imbalance. To cite women, scholars of colour, Indigenous thinkers, and non-Western voices—to be a conscious player of the citation game. However, citing invisibilised scholars shouldn’t be reduced to a gesture of sympathy or a performative act of equity. It’s an intellectual necessity. We should cite them because this exercise sharpens our thinking, deepens our understanding, and improves the quality of our work. Invisibilised knowledge is not lesser but hidden knowledge—buried, unknown, neglected, or dismissed by dominant systems. Why should we constrain ourselves to a narrow epistemic canon when a wealth of insight lies beyond its borders?

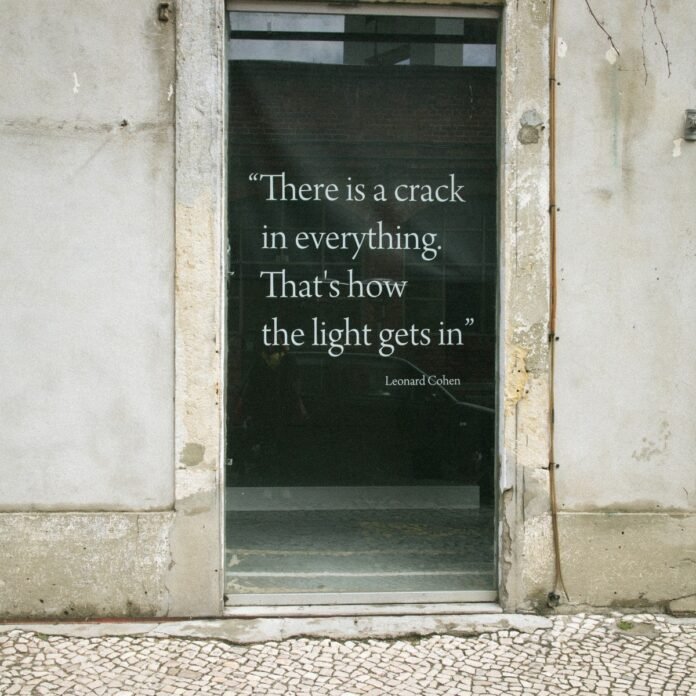

Nevertheless, the intellectual anxiety of missing something persists. But what if this anxiety of being epistemically split isn’t a problem to solve, but a space to live in and thrive? What if this fracture/anxiety/split is a method? Maybe, out of this displacement, something radical can grow—new ethics, alternate genealogies, and fresh ways of thinking, feeling, and knowing. Who knows? Only the future will tell. Let’s think together?

Conclusion

I don’t know how to conclude this. And perhaps I shouldn’t. These reflections aren’t complete enough to be wrapped up. [I would invite you to continue this conversation, here, there and everywhere.] This feeling of being empowered yet constrained by the same system is absurd. It shapes what we read, what we write, what we think, and how we feel and live as thinkers. So, next time you design a syllabus, recommend a reading, or cite a scholar, please pause and ask: Who is this author/scholar? What identities do they carry? Who gets included by default, and who must be made visible through labor? Citations are not just an academic act. It’s political. It’s ethical. It’s personal.

Before I go, I’ll leave you with a few questions that are both personal and political:

- Does this ethical awareness (about epistemic asymmetry) make us more conscious, or just more anxious?

- Is our thinking truly ours, or is it curated by the system we inhabit?

- Are we mainstreaming Western thought by constantly returning to it, even when we do so critically?

That’s it from my end. À bientôt

These thoughts have been simmering through scattered conversations with incredible friends and mentors like Swaraj Barooah (who first nudged my thinking into this direction!), Reeda Alji and Aditya Sharma (my two amazing PhD colleagues at SciencesPo and dear friends), Aditya Gupta, Luca Schirru, and Prof. Aakanksha Kumar—all of whom have helped me see/say things a little more clearly.