Hello Readers,

You might have read about the recent Ranjhana rift. I have a few things to say about that, not on the legal issue per se, but on the much-bandied idea of change of meaning after release.

As I reflect on Raanjhanaa controversy — where both the director and the actor expressed discomfort with how AI altered the film’s ending and, in doing so, its meaning — I cannot help but ask:

“Dear Meaning — Who are you? Where are you? Are you single, in the sense of being stable, definite, unchanging? Where and how do I find you, and more importantly, who assigns you your meaning? Guide me.

As I say with this question, Michel Foucault’s much-cited “author function” comes to mind. As Foucault says, the author is a function that emerged historically around the 18th century, when the figure of the author began to be imbued with authority. Then, the author was not just an individual who penned a text (i.e, a copyrighted work), but the one who became a site of control, someone who anchors meanings to a text, and thereby, controls them once circulated after publication. Of course, cinema as a work of art (a text in a broad sense) came very late, and it’s more challenging to ascertain who the author of the cinema is as well. Yet, the question of the meanings that a cinema supposedly does not leave this modern art untouched.

While we often speak of an author-centric model that supposedly injects a meaning in a work, we tend to overlook another critical figure: the reader who, with the birth of the romantic author, became regulated and disciplined, with her interpretive liberty curtailed, her engagement with the text made contingent upon the author’s intentions and authority.

This makes me bring up Roland Barthes, who famously declared that the author dies at the birth of the text. And I agree. Authors know—whether they admit it or not—that once their work is out in the world, they cannot fully control how others will interpret it. Yet, they engage in a kind of creative suicide by producing a text/work in the hope that copyright law will resurrect their authority and preserve their control. It’s a beautiful irony. Isn’t it?

Still, Barthes’s point stands strong: meaning resides with the reader. G.V. Devy, discussing the history of Indian literary culture in this fascinating book called Crisis Within, also makes a pertinent point. Among several illustrious figures, Devy cites Abhinavagupta, a philosopher from nearly 1,500 years after the Buddha, who believed that knowing the truth was the same as knowing oneself. Later, Dhananjaya’s Natyadarsa further classified plots, heroes, and actions, while Anandavardhana’s Dhvanyalokaer and unchanging (sthayibhava), ultimately leading to liberation (moksha). The upshot is that he saw knowledge not as a fixed realisation but as an ongoing process of discovery.

There’s indeed some force in these observations by Devy and Barthes: if meanings truly and solely belonged to the author, how do we explain the fact that audiences/readers derive meanings that exceed, subvert, or outright bypass authorial intent? Why does fan fiction thrive? Why do secondary works emerge and flourish—so much so that, as Oren Bracha has shown, copyright law only stepped in once these derivative markets gained commercial significance?

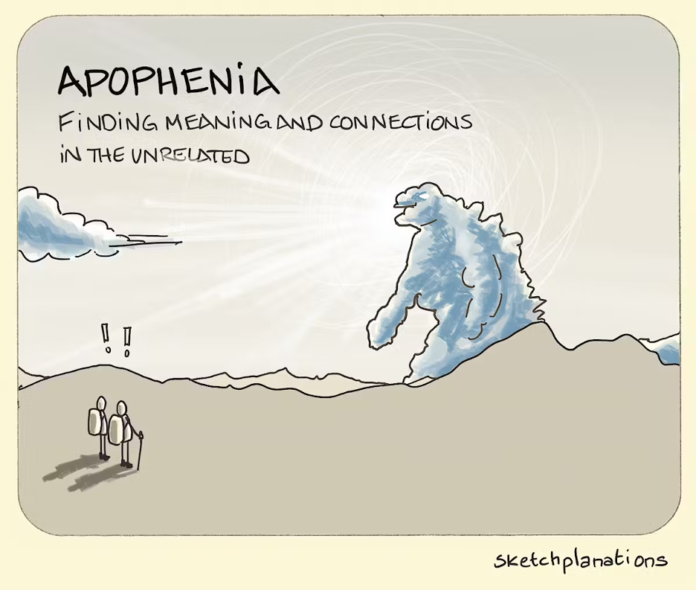

The upshot is this: meaning is anything but fixed. It neither resides in nor emerges from a single creative source. That idea—that meaning originates solely from the author—is a myth. And like all myths, it is powerful! At best, meaning is shaped by cultural positioning and interpretive codes. And more importantly, in this meaning-making game, a reader or viewer is as much a meaning-maker as the author—sometimes more so. Yet, copyright law continues to cling to its fortified fantasies—fantasies we’ve come to believe in, often without question.

Returning to Raanjhanaa, then, I ask again, who infuses meaning in a film? The director? The script or the screenwriter? The actors? The producer? Undoubtedly, there can be moral, logical, and economic arguments to make a case for all or any of them. But let’s look at the director and producers closely—the two main parties in the rift. While the producer is the author by mere reason of being the investor in the movie making, discussing their creative intent is a non-issue. Take the director. Even if we credit the director as the primary creative force, can they alone determine the emotional or narrative meaning of the film? Surely not. A film is a whole which is greater than the sum of its parts. It is a product of multiple voices — actors, writers, singers, director(s), cinematographers — and, crucially, its viewers. Each of these contributors, along with the particular faces, voices, dialogues, lighting, and locations, plays a role in shaping the meanings we eventually come to associate with the film—if we can even speak of “the” meaning at all. (In Raanjhanaa: would it evoke the same resonance if it were set in Guwahati or Delhi instead of Banaras? Unlikely.)

So what happens when AI steps in and interferes with meaning? To even begin answering that, we must ask: what do we mean by “interference”? And more fundamentally, where does meaning reside in the first place? Take Raanjhanaa’s story, for instance—woven with threads of friendship, heartbreak, Banaras, communal rifts, the death of the male protagonist, and a love that is either one-sided or platonic, depending on how one sees it. What makes this narrative happy or tragic? How do we locate meaning in it? Is it the betrayal of two lovers? In the protagonist’s death? Is the impossibility of love fulfilled? Can Zoya be villainised? Not really. Wasn’t Kundan’s obsessive love admirable yet deeply unsettling? Yet again, I’d reiterate that ‘the’ meaning doesn’t emerge from a single character, moment, or authorial intent. (Well… If I were Kundan, I might have chosen death—and perhaps even called it a happy ending. What, after all, is the point of living with someone who never truly loved you, or only did so out of guilt for nearly ending your life? Or, worse, living without the one you loved so deeply you were willing to die for them? Alas. Such is life.) (The lover in me aches to spill some ghazals, shayari—even a verse or two from Rumi—but I hold back.)

Nevertheless, copyright law upholds the notion of a singular “author” who both creates and controls meaning. This belief, especially in an age where AI, with the complexities of cultural production today, deserves to be revisited and definitely doubted. In this context, copyright law as we know it cannot be the sole guardian of textual integrity or meaning.

Having said all that, I remain sympathetic to the claims of directors and actors—not through the lens of copyright law, but from a contract law perspective. When the story of a movie is presented and the actors and directors agree to work on it, they commit to a specific “meaning” or vision of the work. That vision forms part of the basis of their agreement. In this case, that agreed vision was not honoured. Given I’ve not seen the agreement, so can’t comment on that, I feel after this AI-ambush on “meanings of texts/works”, actors and directors ought to modify their agreements and add new clauses. Not sure when copyright law will change to honour the rights of all creators in the movie, contract law can be a more feasible safeguard. What do you say?

That’s from my end.

À bientôt

Image from here – https://sketchplanations.com/apophenia

[ad_1]

Source link